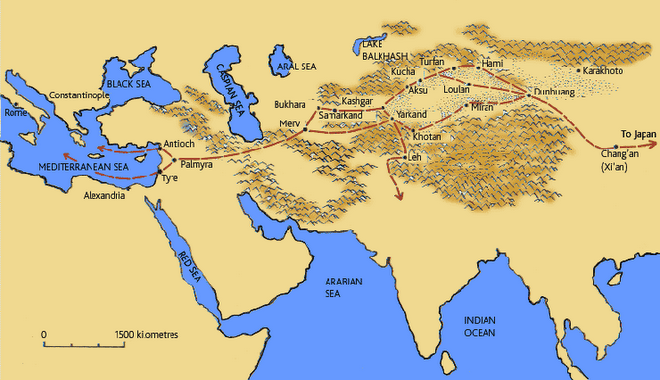

There are many ways to approach the Ferghana Valley. From the North-East, you could follow the Kara Balta gorge out of Bishkek’s own Chui Valley, following the newly cemented road (started by the Turks, finished by the Chinese) through the devastating height of mountains, past rock and a petrified ocean of soft green dunes, to then descend – like the waters – into the patchwork of tamed agricultural land that starts beyond Jalalabad. If however, you are tempted by a southern route from Dushanbe, you will have to weather more stunning and funambulist heights – the vertical Pamir highway to Osh, or the only slightly tamer road through the roaring knife-carved millennium canyons of the Fann Mountains, up and through the hair-pin twists and turns of the Anzob and Ayni Passes, snowed in from October to May. From those wild lonely heights, you start your northerly descent into the madness and beauty of human civilization and Khujand - the 2500 year-old city at the helm, guarding the southern gates of the Ferghana Valley and the wide blue river bed of the Syr-Darya – the valley’s thirst-quencher. Taxer and Commander at the gates, Khujand stands proud, though lately a little broken, a little disconnected by new boundaries and tightened visa-regimes. (There is a sense here that we have splintered our world with nations, fragmented the great plains and their mountains). A more lackluster Westerly approach to the valley will take you from the Tashkent metropole past a slew of police posts and passport checks through the relatively low (2,267m) Kamchik Pass, known to be hermetically sealed to isolate the valley in times of strife (as most recently in 2005 following the Andijan riots when the road was closed for several weeks – the government feared the unrest would pour into Tashkent). This is the fastest route – and despite the police, it is the only one without a border crossing.

These stunning roads carved through height and mountain, lead to the flat fertile elongated bowl of the Ferghana Valley. Here, the earth is rich, dark, damp, the population dense. History abounds as does color, with mostly greens (the cotton only blooms and is harvested in early fall.) The Valley’s land and its fruits are fed by a web of canals – carved out in the 1939 with the muscle and sweat of communist fervor: The Great Ferghana Canal and its tributaries (built in 6 months with the labor of 160,000 collective farm workers). The industrious soviet planners eager to create bumper cotton harvests brought controlled water to the valley. Bringing modern irrigation, they also attracted an ever growing slew of people, ready and willing to work the land. Today, the population density is so great that water again has become gold – a scarce resource that is used and recycled, treasured and fought for. In Rishtan the family I live in walks for about 1 km to get drinkable water for the day. In Miramin’s family home in Istarafshan, drinkable water flows for about 20 minutes each day – enough time to fill up a handful of plastic cisterns. In the summer heat, boys swim naked in the freshness of the canals. Girls, no matter what age are not allowed this cool release. (I’m dying for a swim, but I’ll have to wait for Tashkent’s looser rules to slip into a makeshift bikini.) Entering the Ferghana is also to enter sedentary agricultural and urban centers and their more canonical religions and century-old customs, built and cemented by time.

The valley is a land marked by towns, ambition and tradition. It is dense, alive, pulsing with human stories. It is also a landscape painted with ethnic myths: the residue of historical might and the passage of conquerors. It is a melting pot of cultures, languages and peoples – both complex and beautiful. In his book “Black Sea: the Birthplace of Civilization and Barbarism” Neal Ascherson writes about the rich often explosive mix of cultures that have molded the land around the Black Sea. It is a beautiful description well-suited to the Ferghana Valley:

“Human settlement around the Black Sea has a delicate, complex geology accumulated over three thousand years. But a geologist would not call this process simple sedimentation, as if each new influx of settlers neatly overlaid the previous culture. Instead, the heat of history has melted and folded peoples into one another’s crevices, in unpredictable outcrops and striations. Every town and village is seamed with fault-lines. Every district displays a different veining of [ethnicities and people].”

Cities of legend, founded by kings, rulers of silk and sands, older than Rome, this is one of those pieces of earth at the heart of human history. Osh, Andijan, Jalalabad, Khujand, Khokand, Marghilan, Namangan– the names slip off the tongue in a lullaby of legend. King Solomon, Alexander the Great, Amir Timur, Genghis Khan, Stalin – this is a place where men have left their footprints. But recently these legends and the tracing out of nation states after the fall of the USSR, has left a delicate legacy – a patchwork of ethnicities, the creation of “us, we” and the “others”.

Today Ferghana is a body divided, suspended between three capitals: Bishkek (Kyrgyzstan), Dushanbe (Tajikistan), and Tashkent (the Uzbek bully). If the maps of the region are hard to read, this is no surprise, it is an awkward puzzle of borders and delimitations. It is a body marked by the hassle, stress, prohibitions, fears, taxes and logistics of border crossings. It is a land where sisters, brothers, and parents live across borders, where families are torn by passports and administration. But mostly, it is a place where languages and ethnicity do not neatly fit into the demarcations of borders.

In Kyrgyzstan, of 5 million nationals there are 679,000 Uzbeks (almost 14% of the population), in Uzbekistan officially there are two million official Tajiks, but the actual number is said to be as high as seven million (many ethnic Tajiks are believed to have registered as Uzbeks to avoid harassment), in western Tajikistan there are also large communities of ethnic Uzbeks and Kyrgyz.

Again, reading Neal Ascherson on the Black Sea, you can get a sense of the tension and danger that seems to lie in the ethnic configuration of the Valley (long quote, but Mr. Ascherson writes so well). The quote also hones in on the potential for violence left by the abrupt collapse of the Soviet Union:

“An ancient, ‘multi-ethnic’ community is a rich culture to grow up in. Bosnia was once like that. So was Odessa before the Bolshevik Revolution, or Vilnius, in Lithuania, before the Second World War. (…) But nostalgia makes bad history. The symbiosis has often been more apparent than real.

Living together does not mean growing together. Different ethnic groups may co-exist for centuries, practicing the borrowing and visiting of good neighbors, sitting on the same school bench and serving in the same imperial regiments, without losing their underlying mutual distrust. But what held such societies together was not so much consent as necessity – the fear of external force. For one group to assail or attempt to suppress another was to invite a catastrophic intervention from above – the dispatch of Turkish soldiers or Cossacks – which would pitch the whole community into disaster.

It follows that when that fear is removed, through the collapse of empires or tyrannies, the constraint is removed too. Power struggles in distant places, to which one group or another feels an allegiance, reach the village street. Democratic politics, summoning unsophisticated people to pick up sides and to think in terms of adversarial competition, smite such communities along their concealed splitting-plane: their ethnic divisions. And often, reluctantly at first, they divide. The familiar neighbors, with their odd-smelling food and the strange language they speak at home become part of an alien and hostile ‘them’. Antique suspicions, once confined to folk-songs and the kitchen tales of grandmothers, are synthesized into the politics of paranoia.

All multi-ethnic landscapes, in other words, are fragile. Any serious tremor may disrupt them, setting of landslips, earthquakes and eruptions of blood. The peoples themselves know this, and fear it.”

Nick Megaron, a professor at Cambridge University (quoted on Eurasianet) echoes that fear, saying: “The Ferghana Valley borderlands were once a dynamic and intricate mosaic of ethnic groups, kinship networks, land-use patterns and economic activity. Recent border policies of Ferghana Valley states have shattered that mosaic.”

Governments come to pieces over the land. The valley’s roads, rail, energy and water grids, most designed before borders were drawn and nations built in 1991, nonchalantly criss-cross countries almost indifferent to the political battles they cause today. This land was once the integrated outskirts of the Soviet Empire, unified by ideology and language. Today it is a cut-out, pantomime land, locked in a tug of war. International agencies worry greatly about potential conflict – and recently there have been some. These fears have kept tourists out of the valley, but despite the occasional mumble about unemployment and the surreptitious watering of fields under the cover of dark, traveling there - the valley seems calm.

Still, ethnic strife has exploded in the recent past. Violent ethnic clashes broke out in June 1990 over land distribution in the small, mountain village of Uzgen, in the Kyrgyz part of the Valley and spread to Osh only 55 km away. (This violence is said to have been fostered and fanned by the local political parties, vying for more power). On January 3, 2003 there were riots at the Kyrgyz/Tajik border in the region of Isfara, seemingly over water issues. While staying in Rishtan, in the Uzbek part of the Valley, a fight between two adolescents flamed fears of ethnic conflict in the neighboring city of Khokand – one of the boys had been Uzbek, the other Tajik. The Uzbek boy died – and Khokand was worried about retaliation. Rishtan locals told me that it was just young boys fighting over some mishap in the bazaar, but Khokand citizens, about 40km away were worried enough to believe that such an unlucky skirmish could evolve into something bigger. Indeed, it seems that if some political group has an agenda to promote – these skirmishes could be manipulated and masterminded into violence.

Some of the ethnic violence is also fanned at the highest level. Uzbekistan which provides electricity and gas for Tajikistan’s part of the valley regularly cuts off the supply in the below freezing winter weather – political pressures thus easily exerted. The metal workers of Istaravshan, in the Tajik Ferghana rapidly adapted to this institutionalized harassment and its ensuing daily power shortages, and have reinstalled the traditional hand-powered flame-blowers of their fathers. Better to have low output than no output at all.

Faith

In the Valley too, there are some rumbles of religion.

Fundamentalist Islam is said by many to be stirring in the Valley, and this fear (so greatly enhanced in our global sensitivities since Sept. 11) has been used by the Ferghana Valley governments, especially Uzbekistan to clamp down on many forms of religious schools, gatherings and groups – strikes that often crush pluralistic, non-fundamentalist efforts in its wake. But even USA and Europe-based think tanks take the threat very seriously. The Valley is thought, most notably, to be a breeding ground of support for movements such as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (though it is not clear if the group still exists after the death of its leaders and many members in Afghanistan) and Hizb-ut-Tahrir, which is thought to be popular among ethnic Uzbeks throughout the region. I meet no one in the Valley that openly tells me of their adherence to these groups – but I imagine that it is a dangerous avowal to make.

On quick passage through the valley, it seems the Islamic revival is in renewing spirituality – a people reawaking to the practice of Islam after years of Soviet slumber and religious repression. There are few if any chadors, and calls to prayer are noticeably absent in the Uzbek part of the valley. Faith seems to be translated by gestures and open, honest, proud belief. The breaking of bread and the attending of Friday prayers.

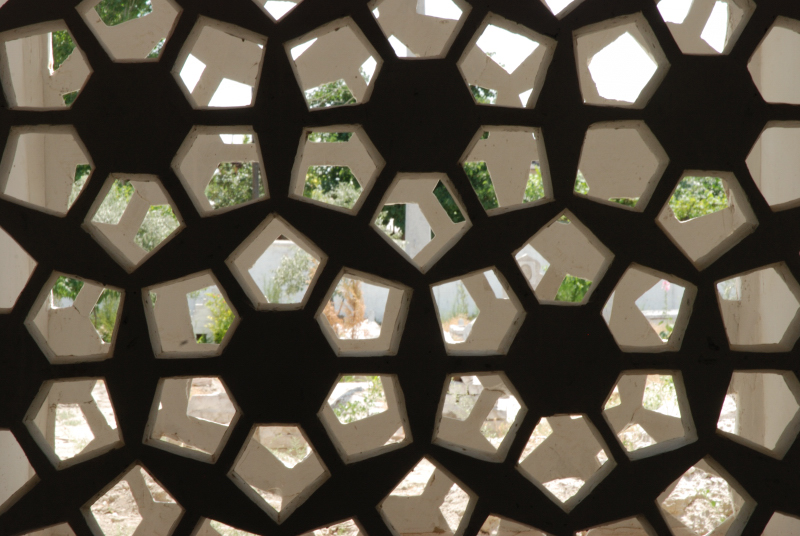

There are some pockets however – like Marghilan, the capital of hand-woven silk – where renewed Islam has reawakened traditionalist thinking and some of the harsher pre-Soviet traditions that formerly held the region. In all the neighboring towns, I am told – almost in a whispered warning - that Marghilan is very conservative. Later, walking unveiled in Marghilan’s streets, I feel an outsider, stared at, noticed. Here Islamic modesty is imposed by the town’s conservative outlook, and people’s glances. It is the first place in the region where the veil is worn formally and with clear religious – rather than cultural – meaning/style. It is also the only place in the valley where my hosts take me to visit mosques and other religious shrines. Many of the boys in the silk factories I visit also take pauses in their work to read Namaz five times a day.

In these pockets, women bear the grunt of traditionalism – I want to say archaic, hard traditions. In Marghilan, the girls get married young: 15 and 16 year old brides are not surprising. Asking a group of girls whether they could finish school and go to university after getting married, one laughs, and says that now her husband’s family compound is her home, her geography. When talking about his son’s upcoming wedding, Fazlidin Aka, one of the silk tycoons in town, tells me that he has found a perfect wife for his son: she is 16 he says, reads Namaz and wears the Hijab.

The late master of silk velvet weaving, Turgonboy Mirzaakhmedov’s daughter Kamberoy, also in Marghilan, was not allowed to continue her university education, despite passing the difficult entry exams and demonstrating her ability and desire to study English. The expense would simply not be given to a girl, and Ferghana University, only one hour away, was considered too far and inappropriate for Kamberoy. Staying at her family’s home for three days, I come to know her and respect her worn beauty, slim and vertical with eyes carved out by lack of sleep. She tells me that she does not want to get married, but that her mom will find her a husband and she will marry this year at 21 – a year later than expected because they could not have a wedding feast for at least one year after the death of her father. In the morning at 4h30, I hear her waking and starting to clean the courtyard. I ask Kamberoy if she wants to come with me to the next towns I will visit, to escape if just for a while. She wants to come, but is not allowed. (It is now her mom who is perpetuating the pressure and restrictions once imposed by her father.)

Mirrors

Beyond some of the harder stories – those stories of women who are not given the space to dream, there is a cool, gargling calm to life in the Valley. Waking to work before the heat, the day starts early. Naps are taken in the afternoon from noon to three, and then tea is sipped in the cool night winds under grape vines. Nights are peppered with dance and song. In Rishtan I drink warm vodka and go to sleep easy. In Marghilan I secretly smoke a cigarette behind a tree. In Istaravshan I sleep with the women and the children of Miramin’s family and am lulled to sleep by the television. In Andijan, I buy strawberries in a night market.

This valley has many lives, always redefined, a collage of mirrors – seeming to reflect what you are ready to see.

Valley: n. centerpiece, critical. a broken puzzle. pockets of countries strewn throughout the land: Sokh, Shakhimardan. (pockets of Uzbekistan scattered in Kyrgyzstan). Warukh, Western Qalacha (Tajik enclaves within Kyrgyzstan), pieces. border crossings. 22,000 flat sq km – a distance from which you forget the mountains. City centers, Ferghana city, Khokand infusing the districts with urban mores. longer veils in Marghilan. Poverty, unemployment, and the daily routine. Women restricted to family compounds, not walking out alone. Craftsmen hard at work, forced to find markets in the tourist towns on the other side of the country.

----

The articles that follow are part of the dance I was privileged to have in the valley, a broken, non-expert, but heartfelt outlook on the valley: a collage of stories.

I did not spend many days in the valley. 3 days in the Kyrgyz slice of it racing between Jalalabad and Osh, 2 weeks on the Uzbek side, and one week on the Tajik heights – but it is a place that marks, that sings. Some parts I entered were alive, glowing, real, others slow, depressed, and almost rancorous. Its crafts are dense beauty, a quilt of colors and harder realities. It is the heartland of traditions reborn, some successfully, others struggling, others dying slowly. Marghilan silk, Shahrihan cutlery, Andijan jewels, mi Rishtan Boys, Isfaran ceramics, Istaravshan calico prints, Khujand embroidery. There are stories to be told here.

Many thanks to the directory “Craftsmen of the Ferghana Valley” given to me by CACSA (Central Asian Crafts Support Association) with which I worked for 3 (discontinuous) weeks in the Valley. The directory, published in 2005 was the work of three crafts associations – CACSA (in Kyrgyzstan), Hamsa (in Uzbekistan) and Fatkh (in Tajikistan) and sponsored by USAID and the Eurasia Foundation. It is an inventory of craftsmen working in the craft centers of the Osh, Jalalabad and Batken oblasts of Kyrgyzstan, the Sogd oblast in Tajikistan and in the Andijan, Ferghana and Namangan oblasts of Uzbekistan. Many of the contributing writers, including Natalia Mussina in Uzbekistan, Svetlana Balalaeva in Kyrgyzstan, and Osmanjon Khomidov in Tajikistan were of great help. merci. merci. Also thanks to Damira Umetbaeva assistant professor at the American University Central Asia in Bishkek for help translating Uzbek, Kyrgyz and Russian.

No comments:

Post a Comment