A short word about Saltanat and her Osh

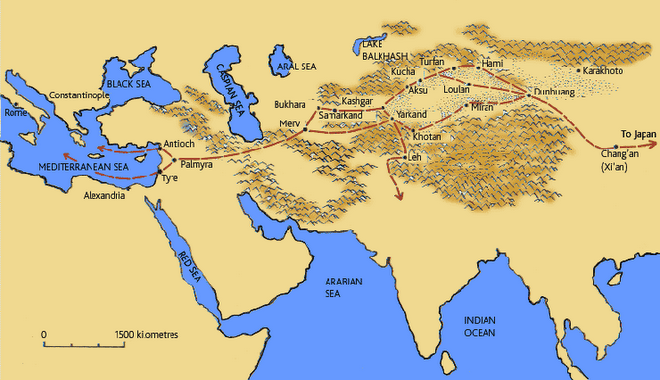

Osh, sprawled around the Suleyman’s Throne mountain: reaching out, ragged, chaotic. Here, we are far from the capital’s control and there seems to be a freedom and chaos unfelt in the north. The streets are a rush, and the bazaar has shed its soviet rigidity to revive its oriental clamor and scents. There is an effervescence of selling and buying, a center of exchange. Chaihana’s, laid-back terrace eateries and tea houses provide easy escape from the bazaar activity and the rush of streets. Here women and men sip their endless pots of tea, chewing on samsa (the Central-Asian lamb-filled samosas, which are found from Xinjiang to the Caspian – perhaps beyond?) and kebabs. We are in proximity to Uzbekistan and the streets here are shared by Uzbeks and Kyrgyz – a proximity that is readily exploited by politicians to cause social unrest and tense days of riots and fighting – as in June 1990. But intermarriage here is not taboo, and many people speak both languages. 400,000 Uzbeks live in the city.

Borders are junctions, meeting grounds. Osh feels like the US/Mexican border town in Orson Wells’ “Touch of Evil”: black and white, mysterious, a little dangerous. In the early evening, we hurry home.

3,000 year old Osh has at its center both spirituality and history. A climb up to Suleyman’s Throne, will throw you into Kyrgyz Islam, infused with ancient superstitions – walking through a cave, sliding a hand over a stone for fertility, circling a tree praying for inner peace. The Prophet Mohammed is said to have once prayed here, and today informal pilgrims walk on the hill’s steep paths. Readers of the Koran wait for a donation, while young people come to catch the cool wind above the city.

Aridity – (or lack of time)

Among this rush and activity, crafts in Osh know little effervescence today. There is no center giving energy to the whole – and so crafts here are still a personal, bazaar-based production. It would be more interesting to go out to see the villages around the city – Gulcho, Karulja, Eski-Nookat, and further south to Batken province (places where I unfortunately didn’t have the time to go – I’m sure the story would change with insight into these regions). But Osh, which stands as the center of those other towns and villages, has not united their craftsmen, or infused the region with an economic outlet or sales platform for the region’s crafts. The town is still missing an organization, a personality to breathe that creative wind. The Golden Valley Crafts Organization, which once aspired to such a role, is now a sad workshop for second-rate ceramics, and has turned towards modern fashion design as a source of income. I meet some felt-makers who make modern Shyrdak for exhibitions as an extra source of family income – but there is none of the passion and inspiration seen in Bishkek or Issyk-Kul. Damira, my translator and I are shocked by one of the craftsman’s poverty – a completely empty house echoing with children’s crying. The family’s four sons are working in Russia, while their wives and children await them here in the two-bedroom apartment on the outskirts of the city. We are looking for some color to take refuge in.

Sultanat brings color to the landscape

Sultanat’s got style. Antique silver rings on her fingers, she’s got a seductive stare, almost nonchalant, but resolute. Feminine, alive. Like many of the women in Kyrgyzstan’s craft industry, she has connections with Aid to Artisans, who first came to the region in the late 90’s to talk about crafts business with local artists and craftsmen. Sultanat worked with the NGO as well as with CACSA, and has attended exhibits throughout the region. She has had her own crafts store for the past 15 years.

Sultanat is trying to support craftsmen in southern Kyrgyzstan, and her small colorful store sells some of their products. Up until now however she only works with craftsmen in the close vicinity of Osh, but recognizes the need for her store to branch out to more villages and towns in the south. She has researched the artisans there, and is aware of their production and knowledge. She would like to expand her business, but says that it will be hard to finance the growth. Already with her present store, Sultanat and her husband lived three years without profit, and mostly live from their paintings. “Financing growth right now will be a risk.” she says, “The political situation is still volatile and that it directly impacts tourism,” – the couple’s greatest source of clients. But Sultanat remains optimistic and is applying for grants from US government organizations to start a five-year project creating an Osh-based crafts center.

Sultanat says that they have now learned how to foster strong partnerships between their store and craftsmen. They know what can be sold, what locals and foreigners demand, and what the adequate price for each object is. She notes that the local government is also getting involved in supporting crafts. On May 28th, a global handicrafts market was held in Osh, hosted by the regional (oblast) government.

Sultanat notes that there is still a clear dichotomy between the cities and villages: crafts production in southern Kyrgyzstan is still centered in the villages while the selling and business of crafts is centered in the cities. Stronger bridges need to be created between both, even if she notes that this may impact the esthetics of the local production. Sultanat believes that it is inevitable that crafts will change. “We are in contact with other countries, other artists, the global world. Kyrgyz crafts will change and no longer be the art of nomads, but of pseudo-nomads. This is inevitable with our lifestyle changes: the functional is becoming merely decorative.” However, Sultanat believes that it is possible and primordial to preserve very traditional crafts. “It is like our language, part of ourselves,” she says. She believes that stores like hers can help to preserve the crafts – enabling local craftsmen to live from their generational skills. She notes that southern Kyrgyzstan needs to start actively supporting the crafts in the Osh and Batken regions.

Talking about the Region

“We are small isolated countries,” Sultanat says, “and we have each developed in isolation.” She says that there is not much interaction in the region beyond what CACSA enables – a handful of craftsmen that attend regional exhibitions. Considering the opportunities, she says, the exchange is minimal. Andijan is one hour away, Marghilan and Ferghana only two hours away, but she doesn’t know the craftsmen there. Despite this lack of exchange, for the first time in Kyrgyzstan, I see some crafts from other countries in her store - Uzbek silk and Tajik hand-embroidered hats. She has made some Tajik and Uzbek partners through CACSA – and so there is some border crossing, but the reality of exchange looks grim.

No comments:

Post a Comment