(map sources: map from le Monde Diplomatic website. their sources: Atlas of the people’s Republic of China, Foreign languages Press, Pékin, 1989 ; Jacques Leclerc, Aménagement linguistique dans le monde, université de Laval, Québec, Canada ; Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Maps and publications, Washington DC ; Recensement chinois de novembre 2000 ; ChinaOnline, Chicago.)

(map sources: map from le Monde Diplomatic website. their sources: Atlas of the people’s Republic of China, Foreign languages Press, Pékin, 1989 ; Jacques Leclerc, Aménagement linguistique dans le monde, université de Laval, Québec, Canada ; Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Maps and publications, Washington DC ; Recensement chinois de novembre 2000 ; ChinaOnline, Chicago.)Below – a short, very fragmented and cursory introduction to Xinjiang: the land and politic of our journey.

Barriers and Beauty

One sixth of China’s territory, Xinjiang is a contested and beautiful place. Wild and ravenous, it is a confluence of mountains, deserts and deep basins. Miles from any ocean, this is a land of dryness, of wind and rock carved by glaciers and the movement of tectonic plates. (the memory of earth). This is land dependent on glacial waters that rush down towards the grape and melon fields of its oases, and then disappear into its deserts. a land of desperate magic.

Proudly standing between 73˚3 and 96˚30 longitude and 34˚10 and 49˚31 latitude, Xinjiang is bordered on the east by the Chinese provinces of Inner Mongolia and Gansu, on the north by Kazakhstan, Russia and Mongolia. To its west are Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan, while to the south, Xinjiang borders Pakistan, India and Tibet.

Pamir, Tian Shan, Kunlun, Altai, Hindu Kush, Fan Mountains, Karakorum – it is a land of mythical names.

This is where the world converges.

But beyond its stunning landscapes, one of the most striking features of Xinjiang is that it is - and feels - contested. Today, by recent turns of geopolitical fortunes/misfortunes, Xinjiang is China’s most north-western province – one of China’s five autonomous regions.

Despite its belonging to the Chinese Mainland however, Xinjiang feels like another land, another country. It is host to 13 minorities, most of them of Turkic descent (Ouighurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks etc.) and is a place of Turkic tongues and cultures. It is a place of golden teeth, scarves, fragrance (the men and women both wear loads of perfume – really nice) and lamb kebabs. It is also a land of faith and religion, and is home to 23,000 of China’s 30,000 mosques.

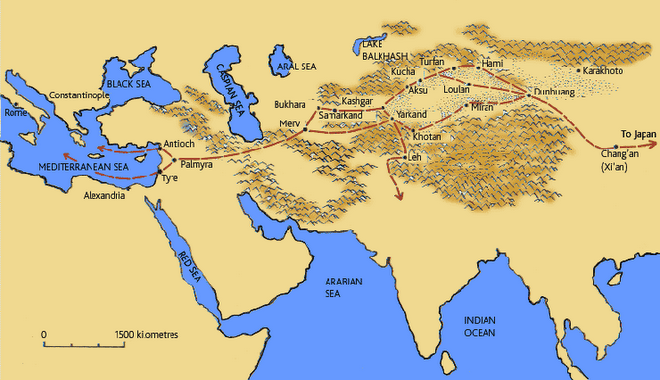

This is the start of Central Asia, the great colossus where Europe and Asia meet.

In Xinjiang this meeting of cultures is more of an explosion than a smooth and fruitful exchange. There is a tension to its streets and architecture, as if there was a constant murmur of discontent. In Xinjiang, and especially in Urumqi, a silent but constant battle is played out, opposing the influx of wealth and economic development brought by the Chinese and the claim by some Ouighurs that this is their country, part of a Pan-Turkic land which is not Chinese. Here is the setting for a complicated battle of identity – Han Chinese are also seen as Xinjiang Chinese, Ouighurs identify with their Turkic brothers, but many who have succeeded in Chinese schools and society, are now Ouighur-Chinese - still neither Chinese and branded by many as less Ouighur. The combinations are many to which are added the complications with other minorities - Kazakh, Hui, Uzbek etc - between whom relationships are also not so clear cut. Xinjiang is the real melting pot of cultures – and a pot that it bubbling.

These latent tensions often surface in violent demands for freedom and autonomy. Battles and strife in the early 20th century led to several proclamations of independence – first in Kashgar and then later in Guldja (today’s Yining) in 1944. More recently riots and uprisings in Kashgar in 1990 and violent riots in Guldja (Yining) in 1996 have once again unveiled the region’s volatility. Some Ouighurs still have independence on their mind – and this January a gun battle in Xinjiang’s Akto County near the border with Afghanistan, resulted in the death of one Chinese People’s Armed Police and at least 18 Ouighurs (branded by the government as terrorists). China blames the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (one small group of Ouighur separatists) for more than 200 terror attacks between 1990 and 2001, causing 160 deaths and 440 injuries. This same group was very controversially added to the U.S. list of terrorist organizations in 2002.

This is a contested land – a territory in which the Chinese are clearly colonizers.

We Shall Shift Geographies

“Communist China’s incorporation of Xinjiang was an attempt to override historical and geographical divisions there within a short time space, and to turn the region into an internal colony.” (Source: Rudelson, Justin Jon “Oasis Identities: Ouighur Nationalism Along China’s Silk Road”. Columbia University Press, 1997). Before 1949, Xinjiang was oriented economically and culturally to the west, with the region’s most important towns Kashgar and Illi facing towards Central Asia’s Fergana Valley and Russia. Distance and harsh terrain made interaction with China scarce.

The communist muscle would brutally shift these cultural and geographic realities.

“The Communist Chinese government sought to fully incorporate Xinjiang into its core political economy (…) Its goals therefore included shifting Xinjiang’s economic and geographic focus away from the west to diminish its trade with the Soviet Union and toward Urumqi and the east. Urumqi was made the transportation hub toward which all roads of Xinjiang were oriented. This new highway network was of immense strategic value for the Chinese. However, it was the westward extension of the railroad in 1962, from China proper to Urumqi that had the greatest effect on Xinjiang. Once the center of Xinjiang shifted to Urumqi, the importance of the cities of Kashgar and Illi diminished.” (note: Rudelson)

This new transportation network would enable China to strengthen its control of the region, shipping in economic goods, settlers and its army. China was to colonize the region with pure numbers – shipping in millions of settlers to populate the region with Hans. (The settling of populations in Xinjiang also helped to relieve the burden of rapid demographic growth in eastern China, that was putting too great a pressure on land in the east.)

The first of the Han Chinese migrants were demobilized Communists troops – quickly followed by train-loads of women from China’s poorest provinces. Talking with Lao Zhang, a Han Chinese whose parents were part of the first truck-loads to arrive, he told me that women were literally shipped into Xinjiang to find husbands among the first Han settlers. On arrival in Urumqi, they were merely assigned a man: a union for the nation. Brutal matchmaking. These first Han Chinese migrants were then followed by unemployed men and women from the Chinese mainland, and later Hans with stigmatized family backgrounds and youths sent to the countryside. Some of the persons displaced by the Three Gorge Dam are also said to have been moved to Xinjiang.

There is a violence to every aspect on Xinjiang’s recent history: brutal matchmaking, migrations across thousands of kilometers, and lands claimed and divided.

Urumqi

Arrival in the mountain Han city. Urumqi could be a jewel in the landscape – slipped as it is between crystal mountains and an expansive plain to the north. But somehow the architects were too hurried by tensions, the urban planners too busied by fear, and the city seems to have forgotten it sits on a natural throne. It is a sprawling mess of cement madness and suspended highways. The city is closed in on itself, and never do the mountains provide rest here.

We exit the train under the cover of clouds, as if there was a conspiracy to hide the Han encroachment of Xinjiang. One train a day. We arrive and quickly disperse. The only reminders of our intrusion are the subtle hands of Ouighur pick-pockets: the obligatory tax of the land.

The Han colonization is a delicate and sad play on lives and hopes: on the whole it is a politic of conquering and economic development, on the personal, it is people searching for new lives and economic opportunities. It seems brutal and unfair that normal people always get sent to the frontlines and burnt in the cross-fires. Here, those people are hopeful Han Chinese sent by their government to people and claim China’s northern frontier. The hope dies quickly it seems, to give place to tense and nervous routine.

Here Han and Ouighur are interwoven, yet not close – an uncomfortable and unwanted proximity.

We stay at Lao Zhang’s apartment, hidden in the dusty and dank backyard of coughing smoke stacks and an electricity plant. His parents came to Xinjiang in 1959 from Henan, arriving after 3 days and nights of bumpy bus rides on dirt roads. They came with the hope and ambition of pioneers, ready to build a new nation, but were quickly welcomed by hardship, -30˚ weather, and the disdain of the local population. But 40 years later they are still here, working out a meager existence in a fourth floor apartment of their factory compound. They have lived a hard life, in a land of violence and scarcity. They have stayed in the brutal urban center – not profiting from the wild beautiful expanse beyond. A wet black soot of a charcoal life among the cold and cement. There is no green here – only the light of tight-knit families and their hospitality.

Lao Zhang left Xinjiang in his youth, wandering to Beijing in hopes of becoming a rock star. Guitar in hand he lived the gritty bohemian life of Beijing’s underground, idealizing Che Guevara and living among the poets and the vagabonds. But this sweet, free and radical existence did not change his stance on the Ouighurs of his homeland – to him – and he openly states it - they are still uncultured and dangerous. Walking through the bustling and colorful Ouighur part of town, centered around the bazaar, Lao Zhang is uncomfortable. He walks as if threatened, never calm, checking his pockets, avoiding contact with the crowd. In the jam-packed Ouighur restaurant where we have lunch, he hesitates to sit down next to a Ouighur man, looking for another place. He says “we” – the Chinese – have helped the local population rise from their uncultured and uncivilized existence. He believes the Chinese have a right to claim the land because they have brought economic wealth and development. (When he talks I can’t help but think of France in Algeria). He has no Ouighur friends, and speaks no words of the Ouighur tongue.

His everyday life is filled with this battle, rocked by this animosity. But a poster of Che still hangs in his hallway. Juxtaposed to his generosity and kind spirit, his stance on the Ouighurs is even more brutal.

This kind of reality shades Xinjiang’s intense beauty with devastating tensions. But some parts are even darker – like the paramilitary town of Shihezi through which we cross on our way to Illi. An all-Han town created by the Liberation Army, it was built on a small plot of wetlands surrounded by desert. The founders dreamed of making – as one of the residents tells me – a city as brilliant as Shanghai. Several people repeat to me that I shouldn’t be scared in this town, its safe they repeat, there are no Ouighurs. (There are many interesting research subjects for those urban-developers/planners/ethnographers – as history and politics are clearly played out in Shihezi’s urban design – especially the staggering volume of its budding industrial development zone).

Shihezi is the center of the Han Chinese paramilitary force – the headquarters of Xinjiang’s colonization. And the power of this paramilitary force called the Production and Construction Corps (PCC) should not be dismissed: “The PCC, with a population of over 2.2 million in 1992, has been a major political force in maintaining Chinese control of Xinjiang. By mid-1982, it had established over 170 state farms and had built 69 medium-large factories. By 1984, the PCC accounted for a quarter of the value of Xinjiang’s total production.” (note: Rudelson)

There is a cold, calculated colonization happening in this land.

Strategic Control

But despite the tensions, the explosions, the drunken fist-fights and ethnic slurs – it seems China will never give up this land - a buffer zone between China’s core and Central Asia.

“The stability of Xinjiang is important to China. It is seen as a test case of central control, relevant to Beijing’s grip over Tibet and Inner Mongolia. Xinjiang is also viewed as a traditional buffer against Turkic Moslem invasions from the North-West. The province also contains three major oil basins: the Turpan, Jungar and Tarim, with up to 150 billion barrels of reserves, according to some optimistic estimates. Last but not least, the People’s Liberation Army maintains numerous bases and nuclear weapons testing grounds in the region, which could be threatened if the Ouighurs gain control.” (Note: Silencing Central Asia: The Voice of the Dissidents. 7/27/01, Ariel Cohen, Ph.D, Eurasianet.org)

……and yet

Within this violent crazy background, we set out into the beauty of the land, searching for the most traditional melodies and rhythms of Xinjiang’s Kazakh minority. We do not enter into the majority-Ouighur world of Xinjiang’s southern territory, and instead head north into the Kazakh Autonomous Region. We dive into color and magic.

No comments:

Post a Comment