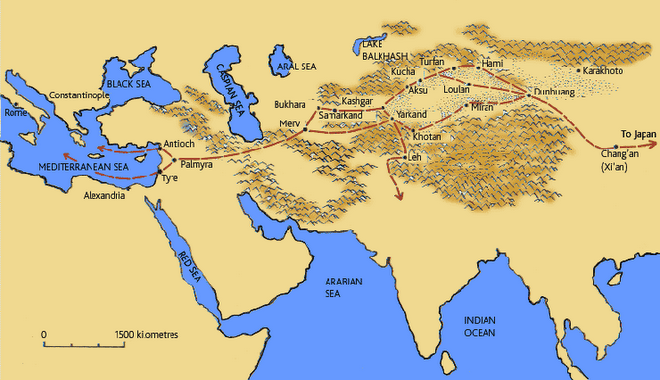

a small detour way south of the silk road, too curious to see some of China's oldest Spring Festival traditions...

Mulian Xi

Mulian XiFollowing the intrepid Sarah O once again (merci sarah) - this time as she sets out to find the rich folkloric and religious customs and rituals around the Chinese New Year in Anhui. She has 15 days until the Yuan Xiao Jie – the major celebration of the New Year’s Festival - when she must be in Shaanxi. I have a little less time before heading out to Xinjiang. Lina, Xiao Bei and Theo have come too, and nights are filled with cool beers sipped on terraces and roof-tops.

We have arrived at Mashan Cun, hitching on the back of a truck, up the hill from Ruo Kang – speeding through the valleys of the sacred Huang Shan Mountains. We walk through sinuous streets, through the winding alleys bordered by beautifully tall two-storied plaster-white houses, past the outdoor pool table and up the narrow path to Ye Zhen Shu’s house. His house stands in the green shade of the century-old magic tree that guards the village with its tenacious roots and exuberant foliage. We are tucked into the village by the giant tree’s gentle architecture and the soft rolling hills around us.

This is the center of Han China – the sacred Huang Shan Mountains – where mist is suspended on green peaks and the Confucian man can seek emptiness, the void, le souffle mediant. This is where the Guqin (traditional Chinese horizontal harp) plucked rare notes to remind the sages of the symbiotic dance of matter and emptiness. Here we could dive into ancient poems trying to find the calm cool peaceful rhythm of the elite ancients - and perhaps this is what the swarms of Chinese tourists come to find in the valley bellow?

An Opera for a Village

An Opera for a Village(I need to get some precision from Sarah for this part – and will update later, but here is a brief introduction to the Mulian Xi)

The Mulian Xi (Mulian Opera) is performed every year at the Spring Festival – we have arrived on Chu 3, the third day of the Lunar New Year and the ritual play is to start tonight. We had been told that it would last three days and three nights. In previous years it could last seven days and seven nights, or up to one month – depending on the needs and wealth of the village. The Mulian Opera is composed of 15 books of song/recitation which are divided into five parts, each with three books. This could easily accommodate one month of acting, or be cut down for the three or seven-day performances.

“The Chinese words xi and ju meaning theatre performance, describe a performance art which is made up of four basic performance skills: chang (singing), nian (recitation), da (military skills and acrobatics) and zuo (doing, ‘acting’).” (note: Jo Riley, Chinese Theatre and the Actor in Performance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997) The Mulian Xi, with its 20 to 30 actors incorporates all four skills, and the actors stamp across stage in movements that have been done for generations. “Jingju (Beijing Opera) is only one of over three hundred different styles of theatre in China and each is defined as a particular style by the type of melodic and/or percussive structure. Each form reflects, to a certain extent, the geographical and cultural influences of a particular area of China.”

In Mashan Village, the Mulian Xi has been passed down by generations for hundreds of years (need to check on the starting date – and who wrote it with Sarah). The ritual play is clearly anchored in the village’s identity; shaping the villager’s conception of the New Year’s Celebrations, their place in history and their village’s place among the mountain. In other villages, people knew that Mashan Village was preparing the Mulian Xi – they identified Mashan with the play, and though they were surprised to see foreigners in this part of the mountain they were not surprised that foreigners were interested in attending Mashan’s performance. The operatic play is one of the key rituals in the village’s New Year Celebration, a ritual that is almost as old as the village. The play clearly presents Confucian values of family, order and political hierarchies and is also a key to propagating cultural and ethical values. In a place where education is less than up-to-standard, it is also a key to learning the stories that are at the base of cultural identity.

In Mashan Village, the Mulian Xi has been passed down by generations for hundreds of years (need to check on the starting date – and who wrote it with Sarah). The ritual play is clearly anchored in the village’s identity; shaping the villager’s conception of the New Year’s Celebrations, their place in history and their village’s place among the mountain. In other villages, people knew that Mashan Village was preparing the Mulian Xi – they identified Mashan with the play, and though they were surprised to see foreigners in this part of the mountain they were not surprised that foreigners were interested in attending Mashan’s performance. The operatic play is one of the key rituals in the village’s New Year Celebration, a ritual that is almost as old as the village. The play clearly presents Confucian values of family, order and political hierarchies and is also a key to propagating cultural and ethical values. In a place where education is less than up-to-standard, it is also a key to learning the stories that are at the base of cultural identity.The play is one of the village’s anchors in time, a way to trace history and meaning. (The magic tree seems to play a similar role, and the villagers believe that if the tree is healthy and continues to grow, so too will the village. as a parallel, if the Mulian Xi tradition dies, so too will the village)

Revival

Surrounded by green hills, tea plantations and pine forests, Mashan village - if not for the newly paved road and the water-gutters full of garbage - seems unchanged and untouched by the cement chaos blasting China. Yet the revival of the village’s Mulian Opera reveals just how intertwined this remote village is with the lunges and leaps of the middle kingdom.

Ye Zhen Shu brought all these old-timers, all men, together and slowly revived the play. Together they wrote from memory the script and the movements: recreating the symbolic gestures and movements on the stage. Blowing life again onto the sacred stage.

This transcription work was not always easy – one of the characters refused to collaborate. He had been beaten and emotionally battered by the villagers during the revolution and felt that he did not want to help the village regain this sacred play. Why should he help the village that had shattered his life? But after drinking rice wine and hearing the pleas of Ye Zhan Shu and other village leaders, he finally acquiesced.

The villagers collected 3,000 RMB among themselves and started the work of sewing costumes, making props and cleaning one of the village’s old theatres.

Bending Rules for Survival

1988, and the villagers were already starting to scatter across the Chinese mainland in search of jobs and opportunities. Men in the village were few, and they would only come home for the week of the New Year’s Festival. Faced with this pressure, the sacred rules of the play had to be bent for it to survive. Women were thus invited to perform. Women, it was declared were now allowed to come on stage, say the sacred prayers and dress as both male and female characters. The play’s ancient taboos were broken, boundaries breached and some mysteries unveiled and lost. 30 students, men and women, participated in the 1988 revival.

The play although revived, still depends on the whims of train-connections, factory vacations and the motivation of the handful of actors. It is still dependent on the small donations of the village spectators and the un-paid devotion of Ye Zhen Shu. (After petitioning for four years, Ye Zhen Shu was able to receive only 1,000 RMB from the local Wen Hua Guan, the Cultural Association, in support of the opera). This year, a three-day performance was planned, but was cancelled after Ye Zhen Shu was seriously hurt in a motorcycle accident and was unable to conduct rehearsals. The village thus waited for the return of the actors and put on the one-night performance they have been performing these past years.

Painted faces and stoic devotion, the play is amateur and almost child-like, with actors fumbling with unpracticed movements and words. It is like children putting on a show in a make-shift attic theatre, both clumsy and serious. The roar and laughter of the crowd brings a palpable energy to the large wooden theatre, and the painted faces of the actors bring an eerie magical feeling to the stage. But mostly the committed serious of the actors, the determination of Ye Zhen Shu and the play’s persistence against great odds, makes it a jewel among the sacred mountain. It is the hope and work of one man that have saved this village’s deepest and most sacred gestures. Perhaps even the magic tree is healthier for the noise and music of that New Year’s night.

There is interesting work to do here.

No comments:

Post a Comment