Central Asia – seen from Beijing (raw notes, a little boring)It’s often said that China is keenly aware of its periphery, and that saying might still be true. China is an empire, and Central Asia is on its western flank.

Although most people in far-off eastern Beijing are hardly aware of the five “stans” that lay to the west, China’s political, military, and economic interaction with its western neighbors is of growing importance. I set out to talk with some experts on the region – to get a feel for China’s policy framework towards Central Asia. Unfortunately, I only talked to foreigners – one Polish, the other Russian – but both were working in Beijing and involved in Central Asia.

A winter afternoon in Beijing, talking with the China head of UNDP’s Silk Road Initiative.

The UN’s Silk Road Initiative has been frozen recently by a lack of funds, and I am surprised by the ineffectiveness of the United Nation’s monolith: visions and great ideas without implementation – dwindling resources and perhaps a loss in international support and confidence. I’m just wondering what will happen if such global institutions falter? Here in this structure are deep knowledge and the presence of great minds – but how to keep them from rotting in offices, unpeopled and empty, wrought by boredom and ineffectiveness? (just a passing note)

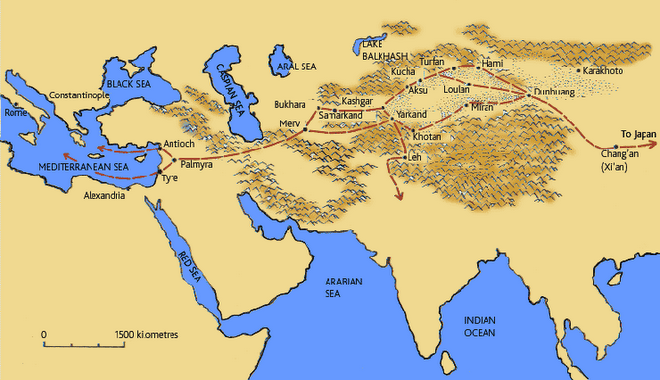

Marketing the Silk RoadThe UN’s Silk Road Initiative is hoping to bring people and leaders together – as in a recent Silk Road Summit held in Xian in June of 2006. The organization wants to build or “market” an image of the region – the Silk Road region – a vast basket willing to embrace all those countries who want to be part of this regional identity, from Turkey to Korea. Mr. Hubner says it is less a historical identity, than a business council with a positive and productive vision for present action and future development.

This marketing work has the goal of attracting and consolidating investments so essential for growth and stability in the region.

The Unexpected

Mr. Hubner knows the region well, and speaks first of its instability – he takes Kyrgyzstan as an example: a country who was “on the right track,” ready and willing to follow the direction of the international community, striving to build a nation, but failing miserably to attract any foreign investment or gain real economic traction. Kyrgyzstan, he says is frozen in its economic crisis, stumbling under the burden of corruption. Kazakhstan on the other hand, Mr. Hubner notes, is building itself on the wealth of oil and gas, with thankfully some of the profits trickling down to the people. The president of Kazakhstan however remains one of the richest men in the world.

This is a region he says that has inherited what it did not expect – left with a political and

economic vacuum, left in havoc by the fall of the USSR. The five Central Asian states were not yet ready to build nations, and had not been trained in independence.

Central Asian countries are still struggling with some basics Mr Hubner notes – such as the symbolic foundations of a nation: languages and the status of history. The five states, Mr. Hubner believes are still struggling with an almost colonial heritage, battling with gifts and chaos. Gifts: first a Lingua Franca – Russian, to communicate beyond boundaries. And then Chaos: economic dependency on the Soviet monolith, and the hardship of suddenly seeking new structures and partners.

China in Central Asia: stability and peace?Asked about China and the Central Asian region, Mr. Hubner directly speaks about the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Mr. Hubner highlights two interesting trends in the SCO. Firstly the organization’s recent expansion to Iran and Pakistan as observer-members and secondly the growing interaction that the organization is enabling for China, India, Russia, and the region.

Central Asia is a crossroads not only for China and the West, but also a gateway to the growing South-Asian market.

The SCO has 6 members: Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. As of 2005, it also has four observer members: India, Pakistan, Iran and Mongolia. Afghanistan has only come as an occasional guest and Turkmenistan is still not involved.

Mr. Hubner highlights the growing importance of the SCO countries as a world block, driven by a common vision and with demonstrated cooperation abilities. As is feared in the West the SCO could potentially be a real opposition to the NATO block. The SCO with its observer members includes 5 nuclear powers and almost half of the world’s population. Enough, I imagine to make the Pentagon cringe.

The obvious strongmen in the organization are China and Russia. Mr. Hubner interestingly notes that China’s interest in the region is mainly anchored in the need for stability and peace. He believes that China is looking to gain insight into this region that is still a “Terra Incognita”. He does not believe that China has any military goal, or targeted “enemies” or expansive goals. Indeed he says, China does not consider that region aggressively, but rather only see’s America as its real challenger on the global scene. Mr. Hubner believes that much of China’s policies (cultural, economic and military) are targeted to building a challenge to America’s hegemony. But Mr. Hubner believes that China’s involvement in the Central Asian region, is indeed only to ensure the peace and stability of the region. China’s main tools up to now have been investment and economic activity.

After September 11th however, the presence of American military bases in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan used for Bush’s offensive in Afghanistan perhaps provide further incentive for China to be involved in the region. Does China see this as American encroachment into its sphere of influence? September 11th literally put Central Asia on the American map of the world. (Bush as a geography teacher). And although the Americans were kicked out of Uzbekistan in 2005 after the US gov. criticized the Uzbek gov. for their brutal handling of the Andijan riots, the American Base in Kyrgyzstan is still up and running, although with a greatly increased rent (up from zero to 200 million dollars). America is also present in the region with oil deals, humanitarian aid, and the regular flow of businessmen and women. – perhaps giving China that itchy feeling.

Of course, Mr. Hubner also notes that Xinjiang is a primordial reason for China’s involvement in the region. Xinjiang looks quiet and controlled, he says, but despite the investments going into the region, there is “always something going on there”. Perhaps China’s knowledge of the Central Asian region can help it deal with the problems and obstacles in Xinjiang?

A New Block – New Principles of UnityThe Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) is seated in Beijing, tucked in between the future construction site of the American Embassy and one of Beijing’s swanky bar streets. Pieces of China’s Central Asian policy framework are formulated within these quiet pastel walls.

Talking with Victor Trifonov, Senior Researcher at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), one thing becomes clear: the SCO was clearly born in opposition to NATO and recent USA international policy.

The SCO’s introductory materials spell it out (with some shoddy grammar - which should be excused as the official languages of the SCO are Russian and Chinese): “In the history of modern international relations, creation and development of “Shanghai Five” represents diplomatic practice of creative value. It initiated new global vision with regards to security, containing principles of mutual trust, disarmament, cooperation and security, enriched new type of interstate relations. (…) This new world vision has raised human society above cold war ideology and made an invaluable contribution to creation of a new model of international relations.”

The SCO introduction further takes a bite at America’s cowboy tactics on the international scene. “As regards foreign policy, the heads (of the SCO) emphasized that the modern world order must be based on the consolidation of mutual trust, good-neighbourhood relations, the abandonment of monopoly and single rule on international affaires; it must follow the prevalent status of principles and norms of the international law.” The SCO countries seem to be clearly aligned against America’s primacy in world affairs.

Mr. Trifonov stresses that unlike the intervention/interference habits of the USA, the SCO agreement very clearly states that the countries in the organization will not intervene in domestic politics or affairs of other member states. (China notoriously lauded the Uzbeks on their handling of the Andijan riots that put the civilian death toll in the hundreds - but internal policies shall not be criticized)

The SCO and the Fight against TerrorismMr. Trifonov highlights that the SCO was concerned with global terrorism long before September 11th and the US’s aggressive plunge into the anti-terror game.

The precursor of the SCO, the Shanghai Five was created to solve outstanding territorial disputes between China, Russia and three of the new Central Asian states. Indeed with the Shanghai Five, China’s borders with Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Tajikistan were all re-drawn and finalized. The initial Shanghai Five, however, was rapidly expanded to include other forms of cooperation and dialogue. The group invited Uzbekistan (which does not have a boundary with China) and created the Shanghai Cooperation Organization for expanded regional cooperation.

Upon its creation on June 15, 2001 the SCO countries cited several new goals, including the fight against the “three evils – terrorism, separatism and extremism.” The SCO had thus declared a fight against terrorism three months prior to September 11th.

The “three evils” clause seems to highlight China’s paranoia that terrorist or separatist groups will enter China through its western frontier. This could indeed be very destructive to China’s gargantuan colonial efforts to keep control of the predominantly Muslim province of Xinjiang. Indeed (in a China-centric view) the “three evils” clause seems to directly target the Uyghur separatists that continue to fight for the independence of Xinjiang. China would obviously want to sever the links between the Uyghurs and their Turkic brothers in Central Asia, and must be eager to gain the support of Central Asian governments in these attempts. The SCO agreement has helped China pressure Central Asian countries to capture and extradite Uyghur separatists who flee Xinjiang. (I’m sure a similar story can be told for Russia and its Chechens, and Uzbekistan and the IMU).

China aside, Mr. Trifonov highlights that Central Asia does have huge geo-strategic salience in the fight on global terrorism. The fight against the fundamentalism, terrorism, and drug/arms-trafficking that seeps in from their southern neighbors – Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Pakistan – is important and pressing. Peace and stability are keys to building an economically strong region – and focusing on terrorism is part of the solution.

(I forgot to ask Mr. Trifonov about religion – and the role religion plays in the organization – Islam, Christianity, Atheism…I think this is perhaps an interesting factor in the SCO meetings)

Eurasian Superpowers: China and RussiaTalking with Mr. Trifonov, it is clear that Russia and China consider Central Asia within their orbits: China and Russia are showing themselves to be the two Eurasian super-powers, eager to both flex their muscle with the help of the SCO and keen to diminish Western influence in the region.

Russia and China each fund 24% of the SCO budget. Each country has 7 representatives in Beijing, while Kazakhstan has 6, Uzbekistan 5, Kyrgyzstan 3 and Tajikistan 2.

The SCO enables Russia and China to inject vital economic support into Central Asia, and the SCO projects are funded by the China Bank of Development and Russia’s New Ekanom Bank. China has pledged USD 500million to finance SCO projects, which range from a trans-Asian highway to hydro-electric power stations, to irrigation projects. Beyond the SCO however, China is also flooding the Central Asian market with consumer goods, construction materials and telecommunications (ZTE and co.). Russia floods Central Asia with its pop-stars, second-hand Ladas and decapitating vodka.

Russian and Chinese influence are converging in the region (the China part being new).

Over the past 20 years, Mr. Trifonov notes, Russia and China have been realigning, and over the past five years, their relationship has been rapidly enhanced. Mr. Trifonov notes that 2006 was the year of Russia in China – a fact that I had not noticed at all - but Trifonov insists it was a great success. 2007 will be the year of China in Russia. An obvious geo-political triangle – Russia, China and Central Asia will undoubtedly become increasingly intertwined. I wonder if Central Asian countries are eager to oblige.