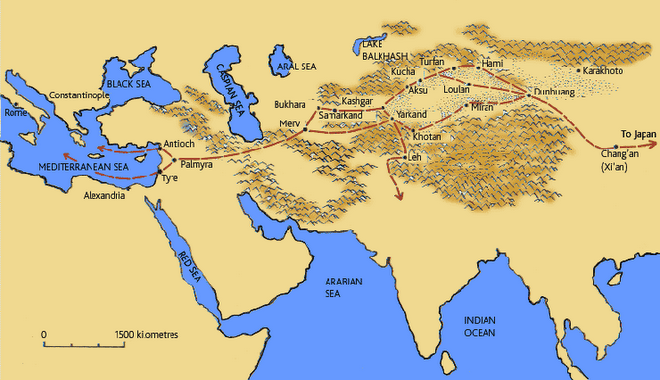

My first interviews with artisans are set around the traditional start of the Silk Route: Xian, the capital of Shaanxi Province. Below is the SECOND of the series on Shaanxi Province.

Art for the People

A cultural revolution needs art. But, how do you find art without looking to the elite, to the group of people with the time and leisure to think and create? Most importantly for the new Chinese communist nation in the early 50’s – how do you find art without history – without the history you are trying to negate or obliterate?

An Unknowing Politician

What is most surprising when talking to Professor Ding is the total absence of politics. He loves peasant painting and seems almost oblivious to the strong political will behind the creation of the Nongmin Hua. He was clearly not the architect or mastermind behind the creation of this national symbol, and reveals himself rather as the unknowing, almost naïve implementer of a new political language. Born in Chenggu about 50 miles west of Xian, Professor Ding was country folk himself. After graduating from his home county’s teachers college in 1955, he was sent as a young cadre to teach in Huxian, where he continued his hobby of painting. One year later, he was chosen as one of the first leaders of the Huxian cultural organization and embarked on the important task of creating a mass art movement.

What is most surprising when talking to Professor Ding is the total absence of politics. He loves peasant painting and seems almost oblivious to the strong political will behind the creation of the Nongmin Hua. He was clearly not the architect or mastermind behind the creation of this national symbol, and reveals himself rather as the unknowing, almost naïve implementer of a new political language. Born in Chenggu about 50 miles west of Xian, Professor Ding was country folk himself. After graduating from his home county’s teachers college in 1955, he was sent as a young cadre to teach in Huxian, where he continued his hobby of painting. One year later, he was chosen as one of the first leaders of the Huxian cultural organization and embarked on the important task of creating a mass art movement.This mass art movement was to turn the gestures of folklore into a national art – into propaganda. The Huxian cultural organization first gathered all those men and women in the surrounding countryside that were renown for their traditional crafts. It then gave the new group a name, and along with this nomenclature an official existence and national recognition. Through this organization, traditional crafts would now be raised to the status of art, and its craftsmen and women would be recognized as people’s heroes. Professor Ding than took on the task of peyang he yindao, training and guiding.

Speaking about this time, Professor Ding is proud and still conveys the full-hearted enthusiasm and optimism with which he embarked on his task of teaching and leading the peasant painters. Professor Ding talks about his countryside students with great esteem and notes the simplicity and beauty of their painting. Tamen hua de shi yuan wer de he repeats in his thick Shaanxi accent, their paintings are naïve and pure – strokes uncorrupted by kuankuan tiaotiao, rigor and rules. The paintings his students created were soon reproduced throughout China – their purity and honesty transformed into one of the communist party’s most powerful tools: propaganda posters.

Speaking about this time, Professor Ding is proud and still conveys the full-hearted enthusiasm and optimism with which he embarked on his task of teaching and leading the peasant painters. Professor Ding talks about his countryside students with great esteem and notes the simplicity and beauty of their painting. Tamen hua de shi yuan wer de he repeats in his thick Shaanxi accent, their paintings are naïve and pure – strokes uncorrupted by kuankuan tiaotiao, rigor and rules. The paintings his students created were soon reproduced throughout China – their purity and honesty transformed into one of the communist party’s most powerful tools: propaganda posters. In Professor Ding’s apartment on the 6th floor of a 15 story building built in the early 90’s in western Xian, we are looking at pictures of the early days of Huxian Nongmin Hua. Flipping through the pages of his album, he stops at each photo and exclaims Zhe Zhang A! At first, I’m not quite sure what he is saying – the Shaanxi accent is like speaking with a mouthful of marshmallows – but almost in a fit of laughter I quickly understand that he is saying - and look, here I am! The pictures depict Prof. Ding, a drawing board in hand teaching his students how to depict the new nation. His students surround him, attentive and respectful. He stops at many of the pictures and proudly explains that they have been published by the country’s leading newspapers. One picture of the him surrounded by his countryside students was reproduced by the Jiefang Jun Bao, the Liberation Military Weekly in 1958, another was printed in the Zhongyang Xinhua Bao, the Capital Xinhua Times a few years later. Huxian’s peasant painting movement was clearly part of the nation’s political machine.

In Professor Ding’s apartment on the 6th floor of a 15 story building built in the early 90’s in western Xian, we are looking at pictures of the early days of Huxian Nongmin Hua. Flipping through the pages of his album, he stops at each photo and exclaims Zhe Zhang A! At first, I’m not quite sure what he is saying – the Shaanxi accent is like speaking with a mouthful of marshmallows – but almost in a fit of laughter I quickly understand that he is saying - and look, here I am! The pictures depict Prof. Ding, a drawing board in hand teaching his students how to depict the new nation. His students surround him, attentive and respectful. He stops at many of the pictures and proudly explains that they have been published by the country’s leading newspapers. One picture of the him surrounded by his countryside students was reproduced by the Jiefang Jun Bao, the Liberation Military Weekly in 1958, another was printed in the Zhongyang Xinhua Bao, the Capital Xinhua Times a few years later. Huxian’s peasant painting movement was clearly part of the nation’s political machine.

The Countryside

At the Huxian Peasant Painting Museum, I am bored stiff. My thin guide Mr. Wang, the third assistant secretary to the director of the museum, asks me if anything is wrong. I tell him somewhat awkwardly that I am not interested in the museum and would rather go to the surrounding villages and talk to the painters themselves. Without hesitation, Mr. Wang surprisingly says hao, zuo ba! great, lets go! He phones a friend, and a few minutes later a van packed with old men pulls up to the museum. We are headed to a wedding, the son of one of the older painters is tying the knot and many other painters will also be present. My visit to the museum was keeping Mr. Wang from some good times with his friends, and he is relieved and happy that he will finally join in the fun. A close call.

More simply, they now also have money. Many are still living off their former days of glory, and have taken on administrative tasks in the museum and the painters association. All however have recognized that the nation’s new king is capitalism, and have entered the peasant painting art-market with revolutionary zeal. They now paint for the millions of tourists that pass through Xian each year, reaping high returns from the sale of their abundant and cheaply made copies. Although he laments the lack of skill and talent in these reproductions, Professor Ding himself has joined this entrepreneurial crowd and runs a peasant painting stall with his daughter in Xian’s famous tourist bazaar near the Great Xian Mosque.

More simply, they now also have money. Many are still living off their former days of glory, and have taken on administrative tasks in the museum and the painters association. All however have recognized that the nation’s new king is capitalism, and have entered the peasant painting art-market with revolutionary zeal. They now paint for the millions of tourists that pass through Xian each year, reaping high returns from the sale of their abundant and cheaply made copies. Although he laments the lack of skill and talent in these reproductions, Professor Ding himself has joined this entrepreneurial crowd and runs a peasant painting stall with his daughter in Xian’s famous tourist bazaar near the Great Xian Mosque. As the next bottles of rice wine are opening, we thankfully leave the wedding. Mr. Wang must accompany journalists from the Liaoning TV station to get footage of someone doing paper-cutting – they are preparing their Spring Festival programming. Mr. Wang tells me to come along. We are going to visit Liu Jin Hua, a 73 year old woman known for her paper-cutting and peasant painting. She was part of the first group of student, assembled in 1956. The TV journalists quickly take their shots and leave. I stay and spend two days with Liu Jin Hua.

As the next bottles of rice wine are opening, we thankfully leave the wedding. Mr. Wang must accompany journalists from the Liaoning TV station to get footage of someone doing paper-cutting – they are preparing their Spring Festival programming. Mr. Wang tells me to come along. We are going to visit Liu Jin Hua, a 73 year old woman known for her paper-cutting and peasant painting. She was part of the first group of student, assembled in 1956. The TV journalists quickly take their shots and leave. I stay and spend two days with Liu Jin Hua.Liu Jin Hua

Liu Jin Hua is in constant movement. Cooking, cleaning, feeding her rabbits, barking at her German Sheppard. She is soft and

Liu Jin Hua is in constant movement. Cooking, cleaning, feeding her rabbits, barking at her German Sheppard. She is soft and  funny - a wide face framed by a grey wool hat and a bright blue mesh of a scarf. Her husband is the Paul Newman of Mafang village, calm and photogenic, quietly sucking on his pipe throughout the day. Together, they are an incredible couple – tender, tough and humorous. Liu Jin Hua is so excited that I am interested in her craft and welcomes me with the concern of a parent and the energy and bustle of a celebration.

funny - a wide face framed by a grey wool hat and a bright blue mesh of a scarf. Her husband is the Paul Newman of Mafang village, calm and photogenic, quietly sucking on his pipe throughout the day. Together, they are an incredible couple – tender, tough and humorous. Liu Jin Hua is so excited that I am interested in her craft and welcomes me with the concern of a parent and the energy and bustle of a celebration. Liu Jin Hua and her husband live mid-way down the second alley of Mafang village when coming from the main road in the direction of Zhouzhi. Their alley, which is about 3 meters wide (and so must probably not be called an alley – but is so because of the dry earth and dust that constitutes its path) is lined with houses facing each other on both sides. Each house touches the next and the alley has become an extended courtyard and meeting place for the residents. The alley is pilled high with bricks and sand, as many families are slowly getting ready to renovate or rebuild their homes. Houses here are status symbols and are frequently renovated and improved to reflect the wealth its owners. Here in Mafang there are three well defined social echelons. The first and lowest echelon is a house that was rebuilt in the 1980’s or before. It is a simple, single-story edifice made out of clay and straw supported by a wooden beam structure. The entry way which does not have a door is a low rectangle painted in black, leading into a large entry room where the kitchen and its corn-stalk burning oven are located. The kitchen oven is connected to the kang in one of the side rooms, and provides heat for the winter bed. (A Kang is a brick bed heated from underneath for northern China’s long winter nights.) Behind the house is a walled garden where there are random semi-permanent structures for keeping animals, tools and kindling – this is the domain of ferocious dogs. For some odd reason, these angry guard dogs are always stationed next to the latrine -- I’m trying to drink as little tea as possible.

Liu Jin Hua and her husband live mid-way down the second alley of Mafang village when coming from the main road in the direction of Zhouzhi. Their alley, which is about 3 meters wide (and so must probably not be called an alley – but is so because of the dry earth and dust that constitutes its path) is lined with houses facing each other on both sides. Each house touches the next and the alley has become an extended courtyard and meeting place for the residents. The alley is pilled high with bricks and sand, as many families are slowly getting ready to renovate or rebuild their homes. Houses here are status symbols and are frequently renovated and improved to reflect the wealth its owners. Here in Mafang there are three well defined social echelons. The first and lowest echelon is a house that was rebuilt in the 1980’s or before. It is a simple, single-story edifice made out of clay and straw supported by a wooden beam structure. The entry way which does not have a door is a low rectangle painted in black, leading into a large entry room where the kitchen and its corn-stalk burning oven are located. The kitchen oven is connected to the kang in one of the side rooms, and provides heat for the winter bed. (A Kang is a brick bed heated from underneath for northern China’s long winter nights.) Behind the house is a walled garden where there are random semi-permanent structures for keeping animals, tools and kindling – this is the domain of ferocious dogs. For some odd reason, these angry guard dogs are always stationed next to the latrine -- I’m trying to drink as little tea as possible. The third and glaringly luxurious houses are entirely made of brick and tile. Once starch white, they have multiple stories and tower over the alley. Liu Jin Hua lives in such a home, and the small gated garden in front of her house makes it the most opulent residence on the alley. Her

living room’s high ceilings are adorned with dusty electric fans and neon lights, none of which are used. In the living room there is enough room for a large round dining room table, similar to those found in every aspiring restaurant in the country. Liu Jin Hua and her husband, however still prefer to sit on low stools and use the tea table to dine. They never use the second floor and have locked all of its obsolete rooms. Their main activity and movement happens between the kitchen and the winter kang in the adjacent room. Liu Jin Hua also has a small painting room on the ground floor, but no longer paints much during the winter cold.

living room’s high ceilings are adorned with dusty electric fans and neon lights, none of which are used. In the living room there is enough room for a large round dining room table, similar to those found in every aspiring restaurant in the country. Liu Jin Hua and her husband, however still prefer to sit on low stools and use the tea table to dine. They never use the second floor and have locked all of its obsolete rooms. Their main activity and movement happens between the kitchen and the winter kang in the adjacent room. Liu Jin Hua also has a small painting room on the ground floor, but no longer paints much during the winter cold.Agile Hands

Liu Jin Hua’s house is filled with color. In the entrance is a large and messy table-alter, strewn with candles, incense and a bright new statue of a Buddhist deity. Behind the alter hangs a one-meter high painting Jin Hua painted about 10 years ago. It is riddled with coagulated layers of bright blues, pinks and yellows depicting the many divinities she worships. It is a thick brute painting that reminds me of the kitsch and beautiful Mexican alters worshiping the Virgin Mary. Nothing here of the Great Leap Forward or the depiction of the new China. She has returned to the roots of traditional painting – the religion and superstition of the Chinese countryside. She once again paints for the village temple.

Liu Jin Hua’s house is filled with color. In the entrance is a large and messy table-alter, strewn with candles, incense and a bright new statue of a Buddhist deity. Behind the alter hangs a one-meter high painting Jin Hua painted about 10 years ago. It is riddled with coagulated layers of bright blues, pinks and yellows depicting the many divinities she worships. It is a thick brute painting that reminds me of the kitsch and beautiful Mexican alters worshiping the Virgin Mary. Nothing here of the Great Leap Forward or the depiction of the new China. She has returned to the roots of traditional painting – the religion and superstition of the Chinese countryside. She once again paints for the village temple. Liu Jin Hua’s paintings are a collage of the countryside’s traditional crafts. She pastes paper-cuts on paintings, and adds bright colorful paints to her paper-cuts. It is a creative mix of mediums, which she says is not her innovation - it has always been done this way she claims. She paints the colorful scenes of the village market, Spring Festival dances and temple celebrations. She transforms every scrap of paper she can get her hands on: a calendar, cardboard, instant noodle wrappings, the traditional thin red paper used for paper-cuts. She is a prolific creator.

Liu Jin Hua’s paintings are a collage of the countryside’s traditional crafts. She pastes paper-cuts on paintings, and adds bright colorful paints to her paper-cuts. It is a creative mix of mediums, which she says is not her innovation - it has always been done this way she claims. She paints the colorful scenes of the village market, Spring Festival dances and temple celebrations. She transforms every scrap of paper she can get her hands on: a calendar, cardboard, instant noodle wrappings, the traditional thin red paper used for paper-cuts. She is a prolific creator. We spend the afternoon sitting on her warm Kang, bundled in blankets. She is telling me stories while gently unwrapping and proudly showing me her many awards. Some half dozen of her paintings were exhibited by the Huxian Peasant Painting Museum and other cultural institutes around China, and she has received a memorial certificate for each time they were displayed. She fires away in her Shaanxi dialect, talking for hours, laughing and eating peanuts. I understand a small 30% of what she is saying and doze off leaning against the wall. When she lifts up her shirt and layer upon layer of long-johns to show me her flabby belly, I have no idea what she is talking about. But I feel that easy proximity and complicity that women often have with each other through their bodies and femininity.

We spend the afternoon sitting on her warm Kang, bundled in blankets. She is telling me stories while gently unwrapping and proudly showing me her many awards. Some half dozen of her paintings were exhibited by the Huxian Peasant Painting Museum and other cultural institutes around China, and she has received a memorial certificate for each time they were displayed. She fires away in her Shaanxi dialect, talking for hours, laughing and eating peanuts. I understand a small 30% of what she is saying and doze off leaning against the wall. When she lifts up her shirt and layer upon layer of long-johns to show me her flabby belly, I have no idea what she is talking about. But I feel that easy proximity and complicity that women often have with each other through their bodies and femininity.Her husband, who I respectfully call old grandpa, comes in with the family’s photo album, and we talk about their visits to Beijing for a Peasant Painting exposition, and travels to the county center. Being part of the Huxian painting movement has clearly boosted Liu Jin Hua’s livelihood and enabled her to be the family’s biggest earner. Her husband worked the family’s fields – 1 Mu (0.17 acres) of land for each person in the family who has an official residence (hukou) in the village. With the support of the peasant painting movement, Liu Jin Hua has traveled once to Beijing, multiple times to Xian and has built the family home. She says that she was thrilled to be part of the movement, and reaped many of its benefits.

Liu Jin Hua tells me that she learned paper-cutting and painting from her mother and other women in the village. Hers are ancient gestures passed down for generations from mother to daughter. I asked her if she had prepared paper-cuts and paintings for her wedding. She says that she had prepared some, but very few. Her husband laughs and tells me that Jiefang qian, before Mao Zedong and his Red Army created the People’s Republic of China in 1949, their families were utterly poor, barely eating enough to quell their hunger. He tells me that I probably can’t understand. Liu Jin Hua continues, saying that at their wedding their were no mian hua, the traditional steamed bread kneaded into beautiful shapes and forms, no musicians or shadow-puppet plays. Her husband’s family could simply not afford it.

Liu Jin Hua tells me that she learned paper-cutting and painting from her mother and other women in the village. Hers are ancient gestures passed down for generations from mother to daughter. I asked her if she had prepared paper-cuts and paintings for her wedding. She says that she had prepared some, but very few. Her husband laughs and tells me that Jiefang qian, before Mao Zedong and his Red Army created the People’s Republic of China in 1949, their families were utterly poor, barely eating enough to quell their hunger. He tells me that I probably can’t understand. Liu Jin Hua continues, saying that at their wedding their were no mian hua, the traditional steamed bread kneaded into beautiful shapes and forms, no musicians or shadow-puppet plays. Her husband’s family could simply not afford it. These traditions call for some basic ingredients, tools and materials which mean they necessitate some monetary investment. Mafang village today is as rich as it has ever been in the past century. In comparison with former years, it is a land of plenty, a land of opportunity. Finally crafts and traditions can be fully indulged in, celebrations can be bountiful and full of magic. But despite these conditions, many of the younger generation are no longer interested in these crafts and ancient forms of entertainment; they are pulled towards the modern and the new, towards cities and their Western-influenced cultures. In Mafang village, no one is learning Liu Jin Hua’s craft, she has no students and none of the village kids come to watch her paint. The young are leaving the village for school and work, they no longer have the time or interest to study these “outmoded and archaic” gestures. Perhaps the loss of these traditions is but a little sacrifice next to the gain in prosperity, and the wealth of opportunities that have come to the village. Perhaps this is the small price to pay for rising up from poverty.

These traditions call for some basic ingredients, tools and materials which mean they necessitate some monetary investment. Mafang village today is as rich as it has ever been in the past century. In comparison with former years, it is a land of plenty, a land of opportunity. Finally crafts and traditions can be fully indulged in, celebrations can be bountiful and full of magic. But despite these conditions, many of the younger generation are no longer interested in these crafts and ancient forms of entertainment; they are pulled towards the modern and the new, towards cities and their Western-influenced cultures. In Mafang village, no one is learning Liu Jin Hua’s craft, she has no students and none of the village kids come to watch her paint. The young are leaving the village for school and work, they no longer have the time or interest to study these “outmoded and archaic” gestures. Perhaps the loss of these traditions is but a little sacrifice next to the gain in prosperity, and the wealth of opportunities that have come to the village. Perhaps this is the small price to pay for rising up from poverty.The second day in Mafang some of the village kids follow me into Liu Jin Hua’s home – this is the first time they see so many of her paintings strewn out on the Kang and they really like her stuff. They are making a mess touching everything and laughing. It’s a nice voluptuous mêlée, which makes me think that these traditions still resonate, are still potent and beautiful. Will some agile hands remain when these kids, ten or twenty years down the road want to recall and reclaim these traditions?

----

(I think of UNESCO and the work of the Wen Hua Guan – the Cultural Associations who have an office in each county center of China – where is there work? what are they up to? – there are so many entrepreneurial projects to undertake here; projects that are both profitable and could help to preserve the invaluable historical and social capital of these traditions. Many ideas and business plans in my head. I feel like only small-businesses and entrepreneurship has the potency to save the ancient gestures of these crafts. There is an urgency for them to be built and developed)

No comments:

Post a Comment