Spirituality, faith and religion are probably not words you expect to hear associated with China – perhaps it would make more sense to talk about “made in China”, cheap consumer goods or A and B shares? Yet, since 1978 and the start of China’s reform years, religion has flourished here at startling speeds. With the end of the chaos and repression of the Cultural Revolution, religious communities once broken and silenced were slowly revived and new converts flocked to the five officially recognized religions in China (Buddhism, Catholicism, Islam, Taoism and Protestantism). According to official Chinese figures, by the turn of the century China was home to more than 200 million religious believers who worshiped in eighty-five thousand authorized venues – a figure which still fails to capture the millions of participants in non-official, underground religious groups and non-official gathering places.

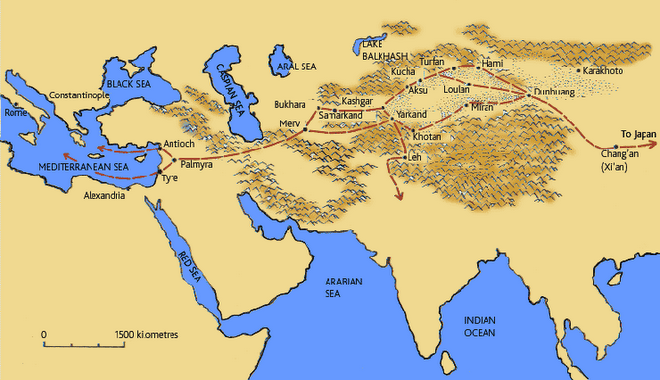

In this context, it seems less incongruent to speak of the growing importance of faith and spirituality – and of interest to me as I step out onto the Silk Route – of Islam.

Lamb Kebabs or a Spiritual Community

Lamb Kebabs or a Spiritual CommunityAsking people at random what they think or know about Islam does not engender many interesting conversations here in the Northern Capital. Inevitably, people answer “bu chi zhu rou, chi yang rou chua’r ah” or “They (Muslims) don’t eat pork, only lamb kebabs”. No mention of the spiritual or historical Islam, no allusions to Xinjiang, China’s Uyghur Autonomous Region home to 8.4 million Uyghurs (a Muslim community known (and feared) in China for their separatist ambitions), no mention either of the 9.8 million strong Hui community, China’s largest Muslim group – let alone mention of the beautiful 600 year-old mosques scattered around Beijing. Indeed to the average Beijing resident, Islam is relegated almost entirely to eating habits.

I imagined that for the 21 million Muslims practicing in China, including the 200,000 in Beijing (stats from China’s 2000 census), this stereotype would be frustrating, perhaps even insulting. And yet, this stereotype of Islam as adherence to Halal rules has been adopted and transformed by Beijing’s Muslim community in many innovative ways.

First, by commercial success. Most of Beijing’s 200,000 Muslims own or work in restaurants – selling Yang Rou Chua’r (lamb kebabs) and Xinjiang’s thick noodles drenched in tomato paste. All claim to follow “Qing Zhen” or Halal standards and provide an interesting alternative to typical Chinese food. Hui minority food stalls – who hawk dishes more familiar to the Beijing palate - are often praised for their cleanliness and are packed with “non-believers”. The Muslim community in Beijing has clearly gained economically from the association of their culture and religion with the rigors of Halal regulations and cleanliness.

Hussein, a shy and beautiful 30 year-old who works in the small family-run Xinjiang restaurant in my neighborhood is from the Salar minority, one of the few Shiite communities in China. He however attends the mosque in Dongzhimen (across from the old long-distance bus station), and is surprised when I tell him that the mosque follows Sunni rituals and practice. Although Islam in China is not monolithic and has been and continues to be influenced by many movements, the majority of Muslims in China are Sunnis of the Hanafite rite (note: Alles, Elisabeth, “Muslim Religious Education in China”; China Perspectives. February 2003 pp 21 to 29). Hussein had noticed some differences but was not really aware of the denominational distinction. Hussein tells me that the difference in rites is not important for him, so long as everyone follows the basic rules of praying, washing and Halal eating. He says that only for funerals and weddings would he want to make sure that he followed the Salar community’s traditions. He further notes that there is not a feeling of minority identity in the Beijing mosque – everyone is Muslim and unified by that fact. He had not realized that the imams at the Dongzhimen mosque were all of Hui minority, and saw no interest in the distinction. This is radically different from Xinjiang, where mosques are often delimitated according to minority and rite (note: Rudelson, Justin Jon “Oasis Identities: Uyghur Nationalism Along China’s Silk Road”. Columbia University Press, 1997)

In Beijing’s Huashi mosque – an early Ming dynasty mosque built in 1414, four years before the Temple of Heaven – the plump Li Ahong (Ahong is Chinese for Imam) tells me that he and his fellow imams do not look to convert non-believers and teach non-Muslims about Islam. He is not shocked or worried that the majority of his fellow Chinese citizens know little to nothing about his faith. Indeed, it makes an all the more tightly knit and exclusive community, whose members can move around freely and anonymously among the city’s masses. As a Hui Muslim (with Chinese Han physical characteristics), Li Ahong can step outside the mosque walls and blend into the city around him. He has no exterior mark of his belonging to China’s thriving Muslim community. Sitting before me sipping green tea from a paper cup on Monday morning, he does look like any Dongbei Ren - a Chinese from the north-eastern provinces: a round, good-humored epicure. Leading prayer last Friday afternoon however, wearing his bleached white turban and flowing coat, it was harder for Li Ahong to conceal his faith, which inexorably differentiates him from other Chinese citizens. Li Ahong explains that he does not want to conceal or hide his faith, but maintains that it is better to have one’s community be associated with Halal rules than terrorism or fundamentalism. Indeed, such a harmless stereotype offers the community in Beijing some anonymity and space to flourish.

In Beijing’s Huashi mosque – an early Ming dynasty mosque built in 1414, four years before the Temple of Heaven – the plump Li Ahong (Ahong is Chinese for Imam) tells me that he and his fellow imams do not look to convert non-believers and teach non-Muslims about Islam. He is not shocked or worried that the majority of his fellow Chinese citizens know little to nothing about his faith. Indeed, it makes an all the more tightly knit and exclusive community, whose members can move around freely and anonymously among the city’s masses. As a Hui Muslim (with Chinese Han physical characteristics), Li Ahong can step outside the mosque walls and blend into the city around him. He has no exterior mark of his belonging to China’s thriving Muslim community. Sitting before me sipping green tea from a paper cup on Monday morning, he does look like any Dongbei Ren - a Chinese from the north-eastern provinces: a round, good-humored epicure. Leading prayer last Friday afternoon however, wearing his bleached white turban and flowing coat, it was harder for Li Ahong to conceal his faith, which inexorably differentiates him from other Chinese citizens. Li Ahong explains that he does not want to conceal or hide his faith, but maintains that it is better to have one’s community be associated with Halal rules than terrorism or fundamentalism. Indeed, such a harmless stereotype offers the community in Beijing some anonymity and space to flourish.We are still in Beijing

Unfortunately, unlike its citizens the Chinese government seems to be acutely aware of Islam’s organic social and political power, and knows that the Islamic faith can be far stronger than mere adherence to Halal rules. Religion, the Chinese government fears could break the symbolic cohesion and order of a society unified under the CCP (note: Kindopp, Jason “Policy’s Dilemma in China’s Church-State Relations”; Brookings Institute). Indeed, Xinjiang and its separatist groups seem to be a constant and irritating reminder to China’s communist party leaders that religion can have a political agenda. China officially blames the East Turkestan Islamic Movement in Xinjiang for more than 200 terror attacks between 1990 and 2001, causing 160 deaths and 440 injuries. Hussein (from neighborhood Xinjiang restaurant) confides that the toll must be much higher and whispers that there is much that happens in Xinjiang which is muffled by the media. After looking over his shoulder to make certain no one is listening, he tells me that Xinjiang could be considered an entirely different and autonomous country. He exhales as if a weight has been lifted from his shoulders. A recent gun battle this January in Xinjiang’s Akto County near the border with Afghanistan, which resulted in the death of one Chinese People’s Armed Police and at least 18 Uyghurs (branded by the government as “terrorists”), acts as a more current reminder that the question of Islam in China is perhaps not simple.

Behind the rapid growth and effervescence of Beijing’s Muslim community stands the constant weight and shadow of authority and central institutions – subtle, but we are still in the capital. “The question of religious education has preoccupied the Chinese authorities since long before September 11th.The increase in the number of schools, the growing numbers of students returning from Muslim countries, the circulation of the writings of reformers from the beginning of the century, which are now banned, the situation in Xinjiang and also the activities of other movements such as those of the Christians and of the Falungong have prompted the authorities to increase surveillance.” (note: Alles, Elisabeth, “Muslim Religious Education in China” China Perspectives. February 2003 pp 21 to 29). All the imams I meet in Beijing are graduates from one of the two Koranic Schools in Beijing, where beyond studying Arabic language, the Koran and other holy texts, they also attend a social studies class on the government’s legislation and religious policy. The imams must also attend regular meetings at the China Islamic Association, as well as frequent inter-faith meetings. Meetings, the imams tell me, that serve to further promote the deep understanding and tolerance China has for all religions – a noble cause indeed.

One of the imams I befriended and talked with on multiple occasions confided that he does not have much respect for the China Islamic Association. We are in his “cell” – the room he keeps in the freshly-painted mosque. It is a small and sober room, whose monastic charm is broken only by the flashing screen-saver of his shiny new PC. Above his bed hang an Arabic inscription and a papyrus painting – remnants of his study abroad in Egypt’s Al-Azhar University. He tells me that many of the China Islamic Association’s representatives are political cronies and that the Association is a hide-away for Hui minority politicians that no longer have influence elsewhere: a cushy retirement lot for out-of-service crooks from another era. He thinks that today’s Association lacks real spiritual commitment, or Islamic knowledge. But he believes that this will change over the next generation, as young more committed Muslims like himself grow to become part of its leadership.

This rigid regulatory framework and power does not only target Koranic students. Indeed minors under the age of 18 are not allowed to pursue religious studies. Talking with Liu Jia Ping, an administrator at Beijing’s leading Hui School, the Beijing Huimin Xue Xiao, this regulation becomes clear. Although the school was recently rebuilt with Arab-inspired architecture and its classrooms adorned with Arabic inscriptions and Muslim symbols, Mrs. Liu tells me that religion is not allowed to enter school premises. There are no religion classes and teachers are not allowed to breach the subject. The only clear sign of belief and faith is again found in the cafeteria – where all 2,200 students, whether Muslim or not eat food prepared according to Halal rules. The school once provided an extra-curricular Arabic-language class, but this too was rapidly closed as the students were already overwhelmed by the very demanding nation-wide Chinese curriculum they must follow.

Demography of Control

The demographic composition of Beijing’s Muslim community – with a large Hui majority - simplifies the government’s work of control in the capital. The Mandarin-speaking Hui (in comparison to the Turkic-language speaking Uyghur, for example) are traditionally more integrated in Chinese society. Although the Hui do have a history of repression in China, they do not hold separatist or radical political agendas. This strongly impacts the overall atmosphere of Islam in the city, creating a less radical, “soft”, more diplomatic and perhaps diluted version of Islam. In Beijing’s Muslim community, for example, the existence of Islamic opposition in the northwest of the country is translated not by fervent support or compassion, but by a reticence to talk about Xinjiang and the presence of fundamentalist Islamic groups in the world today. The Beijing clergy almost ubiquitously announce within the first few minutes of conversation that Islam supports the harmonious growth of Chinese society. They are averse to hearing about Islam’s growing-pains in China.

Upheaval, Silence, and Controlled Rebirth: A Chinese History

Today, Beijing’s more than 75 mosques abound with activity. The Friday mosques are packed with hundreds of people – and Islam is clearly attracting a wide community of worshipers and adherents. Ding Ahong from the Qinghe Mosque in Haidian, north of Tsinghua University, told me that for the recent Eid al-Adha (Feast of the Sacrifice – and date on which Saddam Hussein was recently executed), there were more than 300 people in his tiny mosque, including around 70 foreign students from surrounding universities. He had to lay plastic grass rugs in the courtyard to accommodate the crowd. The worshippers remained in the courtyard, barefoot, as it began to snow. The same day there were more than one thousand worshippers at the Niu Jie mosque, Beijing’s most famous mosque.

Funds for this startling renovation come from a wide variety of domestic and international sources: the Chinese government, the wealthy China Islamic Organization, the World Islamic Development Bank and the generous donations of wealthy Muslim countries, such as Saudi-Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and others. (I need to do more research here into the amount, reach and regulations of international donations to China’s Muslim community, but it seems that substantial funds are flowing in from abroad). Indeed with China’s opening to the world, these countries have been able to more freely support the growing community of worshipers in China. An imam I spoke with, who works in one of Beijing’s leading mosques, tells me that these donations are still closely regulated, and that no faith-based investment organizations are allowed to be directly active in China. In Beijing, much of the money is ciphered through the China Islamic Organization, although the imam tells me that there are also very informal donations made directly to individual mosques. He tells me that if a foreign dignitary visits a mosque he will often speak with the imams and donate substantial sums directly in cash (the imam cites, USD 10,000). On the occasion of his visit to the Daxuecang Mosque in Xian, the King of Saudi-Arabia left an endowment of USD 500,000 to the mosque. Some donations are thus more than substantial.

That money is pouring into this community is clear - it is visible in fresh paint and the many pictures of visiting foreign dignitaries hung on mosque walls. Beyond the early 2006 visit of the King of Saudi-Arabia, Mahdi Karoabi, a speaker from Iran’s parliament visited in 2002, and the late Yasser Arafat met with the China Islamic Association leaders in 1998 - even Libya’s Kaddafi has recently visited China.

Despite the delicate balance, their money, language and spiritual strength have infused China’s Islam with fervor and economic means.

Further adding to the charisma of Islam in Beijing is the youth of its imams. In every mosque I entered, the imams are in their early 20’s and 30’s, young and ambitious. Ding Imam from the Qinghe mosque jokingly suggests that the Cultural Revolution eliminated two generations of Muslims, thus explaining the youth of all the imams. Indeed – during the Cultural Revolution, all mosques in Beijing were closed, imams chastised and all religious practice strictly banned. Numerous imams, I am told committed suicide under the daily pressure of self-criticism sessions and ceaseless violent reprimands. During the Cultural Revolution, only the Dongsi Mosque was kept open for foreigners. The China Koranic School in Beijing was also closed during the Cultural Revolution and did not fully reopen its Koranic studies department until 1982.

The rebirth of the Muslim community is all the more stunning and important within this historical context.

An Inevitably Global Community

In Beijing, Koranic studies are seen as an opportunity - an opportunity to pursue higher education, to find a job and to go abroad. Ding Ahong from the Qinghe Mosque did not have a strong “religious calling”. From a moderately religious family in Dongbei (China’s North East), as a child he attended services only for important celebrations. But when at 18 he was not accepted into universities, the chance to go to the China Koranic School in Beijing seemed like an interesting opportunity. Ding Ahong says that becoming an imam has helped substantially, giving him opportunities to grow intellectually and take an active role in his community. With a humorous grin he says that it also helped him find a wife.

The constant stream of Chinese religious students going to study abroad is only rivaled by the amount of students from the Arab world who come to study in China (I have not found stats citing the exact number, but they must exist). These exchanges inevitably bring flows of ideas and new streams of thought, exposure to different doctrines and religious practices. The imams I talk to in Beijing maintain that the students returning from study or work abroad do not bring back any radical thought or new doctrines, and would not have the power or freedom to change a whole community. I wonder if this is just the official line, and imagine that in a small community in China’s north-west, such new knowledge and world experience could bring about substantial change.

The growing exchange, links and support from the international Muslim community is a China-wide phenomenon. Students from each of China’s ten Koranic schools are seizing opportunities to go abroad, and those opportunities are increasing. In 2003, while traveling in Gansu province in a remote underdeveloped town, I bought some crisp sugar cookies from a quiet very stately Hui woman. She reassured me that she would not “rip me off” with western tourist prices. When I asked why, she told me that she was a Hadji - had completed her pilgrimage to Mecca. She told me that her daughter had also found an opportunity to leave the hardship and trials of the town with a scholarship to study in Malaysia. In a town close-by, as I stumbled into a newly built mosque a sole male student about 10 years old was using his summer vacation to study Arabic with the local imam. The imam told me that this way his student could hope to receive scholarships to study abroad. While most of the other students in this town could barely dream of going on to study in Beijing’s universities, the imam’s young student was already aiming for the Middle East. Islamic learning is clearly creating opportunities for growth, learning and study abroad for believers throughout China.

With its five pillars of faith – and most notably the call to perform the Hadj - Islam inevitably creates a global community. China’s Muslims are turned to Mecca in the West in both the physical orientation of the Mihrab and the dream of pilgrimage. Today with the opening of China’s economy and increasing financial support from the global Muslim community that dream is all the more accessible and real.

10,000 Chinese Muslims perform the Hadj each year. These 10,000 Hadji return each year to their mosques, communities and families throughout China bearing witness to a powerful experience of faith and the knowledge of the global Muslim community. They return with new religious commitment and global contacts that will doubtlessly have a deep impact on China’s Muslim community. What role the community will play in China’s international relations and the extent of penetration of foreign Islamic movements remains to be seen, but the next few years will perhaps bring interesting shifts and turns.

….if you have read this far, thank you! I promise that there will be more succinct entries in the future...

No comments:

Post a Comment