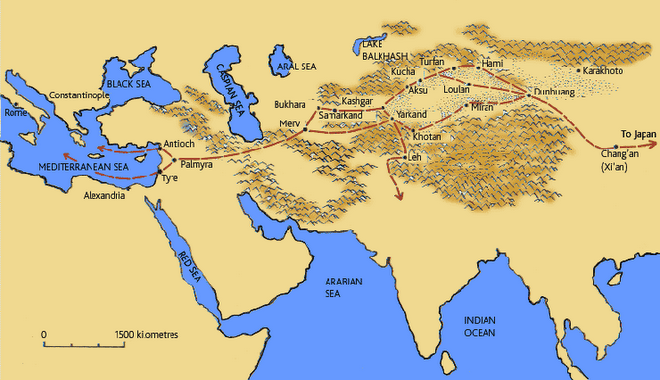

My first interviews with artisans are set around the traditional start of the Silk Route: Xian, the capital of Shaanxi Province. Below is the THIRD of the series on Shaanxi Province.

Yabai Zhen: Hands and Needles, Threads and Machines

Yabai Zhen: Hands and Needles, Threads and Machines“Yabai Zhen is the unchallenged center of embroidery in northern China,” I had been told. “It is the heartland of needlework, the capital of stitching and sewing.” With the help of these descriptions and a large heap of optimistic naiveté, I had imagined the town alive with color and chockfull of old women’s handiwork: a bustling hub of traditional crafts. So when the next day I cruise into this decadently dusty and garbage-strewn town, I have to remind myself that sometimes places are hard to pierce, that the surrounding villages need to be discovered, that I should not despair yet. This town feels as if it has fallen from grace. Tall buildings, once freshly painted are leaning towards the gutters, their facades sagging with the rusted rivers of last year’s rains. It feels like a deserted ballroom invaded by uncomely squatters: dusty, dirty and unwelcoming. The bleak whole is traversed by a dangerous thoroughfare down which buses howl and honk, not giving the town’s streets a second glance. I decide to get off the bus anyways.

I walk down the desolate main street, derelict and almost abandoned but for a few shops open for this Friday afternoon’s slow business. I am wishing that Mr. Liu the talkative shoupolar garbage collector I had met in Mafang village was still working here. At least I could have some company to slurp noodles or doufu nar, tofu soup. I sit down to lunch at a low table in a dent of a restaurant and eat pickled vegetables and a plate of dumplings. There is a collective gasp of surprise among the restaurant’s customers and everyone turns to stare – they too are wondering what the hell I am doing here. First some basic questions, some praise at my use of chopsticks (yong de hao de hen!) – and then everyone in the restaurant is conspiring to help me find handicraft embroidery. Each person has a plan and firmly-set ideas; they are battling about where I should start looking. I am finally taken hostage by the winner, an old woman who takes my arm and pulls me out of the restaurant. She knows a handmade embroidery workshop on the outskirts of town, and parades me through town until we reach it together.

This is how I meet Mrs. Zhou, in her one room workshop attentively watching the buzzing needles of her 12-headed computerized sewing machine. True, she does occasionally manually fix the threads and notches of the machine, but there is no hand-sewing to be found. She and her husband left their work at a local factory two years ago to buy this 3-meter long computerized sewing machine and set up their own business. They invested RMB 70,000 for the machine whose computerized designs they now sell for RMB 1.5 per piece, each piece having up to eight three square inch flowers or other designs. Jiu shi ku de hen she says, this work is really hard and time consuming. They are able to make about RMB 200 (USD 18) per day; just enough to support their family and reimburse their substantial initial investment. Electricity only costs about RMB 300 per month. They communicate with their clients by phone and have enough regular clients that come seek them out, so that they do not have the additional pressure of attracting new business.

A Sewing Economy

Everyone in Yabai, I soon discover, has something to do with embroidery. Indeed the whole economy of this town is centered on sewing – from threads, to sewing machine equipment, to needlework, to finished products like sewn blankets, door hangings, comforters and pillow-heads. Here is where all of China’s kitsch bed-wear originates. The wealth of Yabai’s 15 outlying villages and its population of 5,000 persons once fully rested on the bustling sewing economy of Yabai town-centre.

Ms. Zhang and her husband however have been adamant and successful entrepreneurs – taking advantage of the remaining embroidery market, while also diversifying to other more promising markets. Over the past two years the couple has sold 30 of the 40 computerized sewing machines in Yabai. They have also set up a customer service store where they sell the thread and repair parts needed for the machines. They have a small factory in the back of their home, where 10 workers help to dye and package the thread they then resell in town. This is a lucrative business, and the couple and their son have traveled to China’s key tourist destinations every year for the past four years. They still however do not have a shower in their home, and go to the County Center every third day to shower together. Today, they are getting on board China’s growing “green economy” and are looking to plant trees and shrubs to sell to China’s cities as they start to beautify their streets and parks. This has already very successfully started in some of the villages around Yabai, and they want to get into the action.

The couple is also wagering substantial cash into the production of embroidered patches figuring the 2008 Olympic mascots. They do not have an official agreement with the Olympic committee, and will be using the mascot logo illegally – like thousands of workshops around China. I imagine that over the next 18 months, thousands of computerized sewing machine heads will be working in a frenzy to produce the mascot accessories to be sold around the world in the summer of 2008. Perhaps there will be enough embroidered mascots to build a path to the moon: 1.3 billion pieces at least.

Hand-Embroidery?

I continue to look for hand embroidery and ask the director of the Wen Hua Guan, the Cultural Association in Zhouzhi County (the county under whose jurisdiction Yabai village is under) for some leads. He tells me in a surge of honesty, that even though Yabai is called the heartland of embroidery, the name reflects a modern phenomenon started in the1980’s. “The embroidery here,” he says, “is not outstanding; it is just like in any other part of China: a long tradition of woman preparing their dowries.” This fact he has conveniently omitted from his official report to the provincial government, a report of which he has given me a copy. In the report the Zhouzhi Cultural Association asks for RMB 900,000 to save the embroidery tradition of the town and its surrounding villages. I am astounded by the substantial amount of this four-year budget (2006-2010). Having visited and observed the Cultural Associations of several counties, I have seen that their work is minimal and almost derisory – their’s is a political hide-a-way, a joke of a responsibility, a comfortable vantage point that comes with chauffeured car and endless banquets. To top it off, this is the budget the association has asked for only one craft – they have of course also drafted budgets for all the other crafts of which traces are found in all the surrounding villages! Who will drink and eat this money away, I wonder? I doubt that it will ever sift down to the countryside and those people that can save and teach this ancient tradition.

Back in Yabai, when I ask where I can find people who still hand embroider, everyone insists that no one continues to hand-sew in Yabai. One woman tells me that the oldest embroidery technique used here is the foot-powered sewing machine. But when I ask Zhang Zai Fang’s 54 year old mother-in-law if she has any pieces that she has hand-embroidered herself, she proudly says yes. 10 minutes later, she comes out of her back store-room with a beautiful hand-sewn menliar or decorative door curtain. She sewed the intricate flowers, birds and trees on this door curtain for over one month in preparation for her wedding. At the time, each woman was meant to sew a door curtain, several pairs of pillows, a duster and a comforter for her wedding-day. These dowries were hand-sewn treasures. “Woman then had time,” she says. “We would sit at home with friends chatting and sewing. When there was no farm work, we would sew.” As little as three decade ago, there was no notion of market deadlines, no stress, no rush, no production quotas and targets. There was only time and the movement of needles. Today, due to her bad eyesight and arthritic hands, the fifty four year old no longer embroiders. None of her daughters have learned to embroider. There is no market they say. No one is interested in hand-sewn products anymore. The computerized sewing machine is king.

Back in Yabai, when I ask where I can find people who still hand embroider, everyone insists that no one continues to hand-sew in Yabai. One woman tells me that the oldest embroidery technique used here is the foot-powered sewing machine. But when I ask Zhang Zai Fang’s 54 year old mother-in-law if she has any pieces that she has hand-embroidered herself, she proudly says yes. 10 minutes later, she comes out of her back store-room with a beautiful hand-sewn menliar or decorative door curtain. She sewed the intricate flowers, birds and trees on this door curtain for over one month in preparation for her wedding. At the time, each woman was meant to sew a door curtain, several pairs of pillows, a duster and a comforter for her wedding-day. These dowries were hand-sewn treasures. “Woman then had time,” she says. “We would sit at home with friends chatting and sewing. When there was no farm work, we would sew.” As little as three decade ago, there was no notion of market deadlines, no stress, no rush, no production quotas and targets. There was only time and the movement of needles. Today, due to her bad eyesight and arthritic hands, the fifty four year old no longer embroiders. None of her daughters have learned to embroider. There is no market they say. No one is interested in hand-sewn products anymore. The computerized sewing machine is king.

Yabai’s Countryside: Kiwis and Celebration

Motivated by this first hand-sewn discovery, the next morning I decide to borrow a bike and peddle around Yabai’s countryside. I have given myself two days, and am determined to find women who continue to sew by hand.

The countryside around Yabai is bustling with activity. Everywhere people are cleaning, cooking, and getting ready for next week’s Spring Festival. Villagers are flocking to the county center to buy new clothes for their kids, firecrackers, fruit and other New Year’s gifts and luxuries, while their family members are returning from the big cities where they have gone to work or study. The whole country is alive with movement. This week the trains are running packed and at full throttle through the great Chinese Mainland: Iron Dragons connecting cities to the countryside. The world has shifted from the Roman calendar to the traditional Chinese Lunar calendar, in which the Spring Festival marks the first month of the year. There is a palpable excitement: families reunited, stories told, and nights filled with color and light. The countryside has visibly dug into its bag of traditions – emerging are paper-cuts for the windows, painted deities for the houses, and the village troupes are getting ready for the festival’s Shi Huo, the crazy drum accompanied dances and songs performed on the fifteenth day of the first lunar month for Yuan Xiao Jie. One village I ride through has put up a giant swing for the kids to play on. The first crackers are lit, and the villages are animated with the sound and color of celebration.

The villages I ride through are surprisingly clean and orderly. Only 30 minutes from Mafang village, they have a distinctly different style and are clearly more affluent. Yabai’s successful sewing market has clearly shared its achievements. It was only three years ago however that each village got a cement road, leading from the village’s center to the main Zhouzhi to Yabai road. The villages are arranged radially from this central and economically powerful axis – I imagine that it has been this way for centuries. Roads have always been the most basic necessity for trade, commerce and economic subsistence. Next year each village in the county will be able to choose one additional road to be paved by the county government. Road by road, economic growth is reaching the countryside, boosting its connectivity and the speed of movement and ideas.

Yabai’s countryside hides another sweet surprise: kiwis. In almost each village, there is a courtyard full of people frenetically packing kiwis into bright jazzy Spring Festival packaging. These tasty kiwis were first picked ripe in October and have been kept in the warehouse’s cooling rooms for 5 months, waiting to be sold at the high prices enabled by the Spring Festival. Les malins! Huge trucks are waiting in the villages to deliver these kiwis to festival tables throughout the country: Jiangsu to Liaoning. This is a lucrative business for the kiwi field owners – which are often joint-ventures run by several village families together.

The workers packing the fruit however, are the poorest from the surrounding villages. The women earn RMB 15 a day, a little less than USD 2. The men, who perform the more strenuous work of lifting and carrying the crates earn a double wage set at RMB 30 for their more than 10 hours of work. This is the countryside’s harder side - the underbelly of the world. These are the people without growth opportunities, the ones who have not yet reaped the benefits of cement roads and the past 30 years of growth. These are the people who will not pause at the Spring Festival, for which work is still basic survival. These people are the hard reminders that despite all of China’s growth and success, there is still work to be done, there are still growth opportunities to capture.

Yabai’s Countryside: Dowries and More Recent Math

The village doors open. I am taken into houses while women sift through their closets and piles of old pillows, comforters and blankets looking for their old embroidered handiwork. They pull out the remaining pieces of their dowries, sewn thirty or more years ago. They are beautiful and speak of older times – times when these villages were still isolated geographically and economically. They speak of time and rest and communities at work. Almost every woman I meet is eager to sell these pieces to me, and they are disappointed when I tell them that I am not looking to buy. Many of the women in the villages tell me that they have already sold off most of their most beautiful pieces: antique collectors have already scavenged through these villages, buying beautiful pieces at meager prices. One woman tells me that three years ago she sold her mother’s dowry door curtain for only RMB 20. Her mother had worked several months on the piece, and the daughter now regretted having sold it. The regrets were not for the sentimental value of the lost piece, but rather for the higher price that she could have captured for it today.

An intricately embroidered door-curtain in good condition can reap up to RMB200 in the villages these days. They are then sold, I imagine, for triple that price in urban and foreign markets. I ask some of the women if they don’t want to keep these pieces for their daughters, for future generations – but they are not interested in such inheritance. They want to give their daughters economic and educational opportunities, not the antiquated symbols of former hardships and darker days.

Today, door-curtains still hang in every villager’s house. But they are the bright fluorescent modern variety, computer sewn for the masses. Why do women not continue to embroider by hand, I ask. The reply is brute: it’s simple math. It takes one month to sew a door-curtain which in the local market she can only sell for RMB 200. A woman packing kiwis in the village however can earn around RMB 450 per month. The math is indeed simple: more kiwis, no more hand-embroidery. There is no time to think of heritage, of traditions: there is no value for cultural capital set into the equation. Here survival, education, growth, and “getting out of here” are the keys.

Many of the formerly prolific embroiders I meet, old women in their 60’s and 70’s no longer embroider because of their deteriorating eye-sight. However, this retired community of creative women is still active, sewing thicker, simpler toys, tigers and shoes for their grandchildren and village kids. Some of the old women I meet also continue to sew the colorful pillows and feet-holders made to assure the comfort of the dead in their wooden caskets. This is a market that never fades: anchored in birth and death.

These women go down to Yabai’s market held every three days to sell their wares. A pair of baby shoes is sold for RMB 5, a felt tiger stuffed with corn stalks, to celebrate the newly-born’s manyue first month goes for RMB10; a pair of hand-sewn shoe-soles are RMB 1 – the price of a bus ride home. All these prices can be tripled in Beijing, and again quintupled in New York and Paris.

In Yabai, I’m learning that keeping these traditions alive is math, geography and movement.

A clear obstacle to the perpetuation of hand-embroidery is that these creative women lack the links and connections to the wider – city and international markets – in which their hand-embroidery could reap more interesting prices. To link their local supply market to outside demand would be enough to create a flourishing trade for the ancient craft, enough to save some of these ancient gestures, and teach them to new and younger hands. Again, where is the Wen Hua Guan, the local Cultural Association? I’m thinking that I should send them a business plan for their RMB 900,000. With that much money, we could hit the international market within 6 months.