The beginning

We forget often the origins. Those places where everything starts: a change in the land, a mulberry tree that has seen the shifts in the waters, its trunk knotted in the wisdom of years, in resistance, a glance.

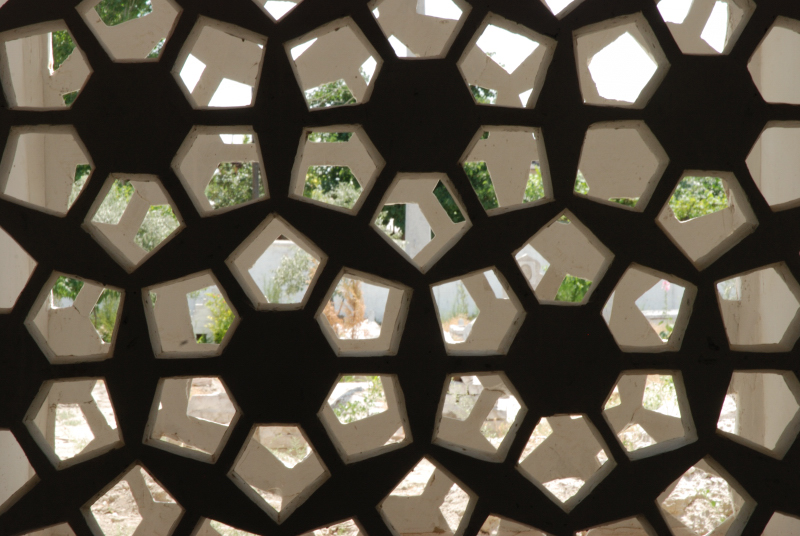

Here in Marghilan things start in courtyards, houses built to provide shade and cool. They are a succession of verandas, terraces, and rooms kept dark with linen veils: a cool cavernous realm. We are in Mirzaahmedov Usto’s house. Closed onto itself, it is a private world within four walls, in the middle a courtyard garden for green and sky. But walls mark clear geographies. No windows give out onto the street and the architecture, like the life of its inhabitants is turned inward, centered on family.

The home compound is a fortress, built in retreat from the weight of sun and outside glances. We knock and call before entering. The women do not leave without permission. We are not like kids – we have interiorized the reflexive now almost intuitive barriers that our age mandates we acknowledge. At night I write in my notebook: little girls are already women, adopting the limited geographies of their mother’s: domestic prisons. But there is also a comfort in walls; a safety. Here we are protected and kept from that wild world for which we have constructed so much fear. We are out of reach of outsiders, stray dogs and the violence of unknown men. (These days, I feel a brick batise being built around me. Walls rising, imperceptible but real, like a shaking, a rumbling of which I am the architect. Sewing my own Paranja. (Paranja - the local chador once worn by women in the Ferghana and throughout Uzbekistan before Soviet times).

And yet in this clearly defined and self-contained space there is passage, there is color and all the pain, fantasy and happiness of human lives. Family members trickle in throughout the day: cousins, their children. Older men come more formerly, waiting at the door for an escort into the middle, the womb, the heart of the family.

Here, in this courtyard in the middle of Marghilan starts a story of silk

A Kingdom and its Princes

In Marghilan, silk is the center of the universe – its legends and practical magic are wrapped up with the realities of the town. Stay here a couple of days and you can get a first sense of both. In its fine woven threads, dyed and intertwined, silk carries the economy of the town, its livelihood, its hierarchies, its dynamics. To the silk is tied power, religion, ambition, opportunities and the balance of women and men. In Marghilan, silk is like history – fluid, luxurious in its complexities, brutal and manifold.

Everyone in Marghilan is connected to silk weaving. From the raising of silkworms, harvesting mulberry leaves, the preparation of thread, the designing, the weaving, to the selling – the city is centered on the craft.

Fazlitdin Dadajonov is a prince of silk and the director of his self-made Ikhat National Craft Development Center. Entering Fazlitdin’s house, we enter a palace. We are brought out of the sun into its cool rooms, where we are served fresh pistachios (a curious discovery for me), chocolates, walnuts and all sorts of succulent dried fruits on precious blue porcelain dishes.

We enter abundance and tradition – sitting cross-legged on the ground sipping luxurious mineral water and scented teas.

Fazlitdin is a fourth generation silk weaver. He sits boldly and has the proud stature of a man who knows his place in the world – on top. He is very impressive with his scissor-cut features and his crisp white shirt. Money is folded up in his shirt pocket.

I write in my notebook: “Fazlitdin is smiling and laughing, talking about his spirituality. He is a prince receiving us. I wish that I was wearing gold, had dark charcoal eyes and smelled of rosewater. Can I say: one minute Sir, we have been on the road, we need a sweet honey shower.”

Sitting and talking with Fazlitdin through the afternoon is to be faced with paradoxes – many. When he talks, he never looks me in the eyes – a constant reminder of my sex. feminine, inferior. And yet he is exuberant in his hospitality, answers my questions with interest and is engaged in our conversation. We are invited to a copious lunch, and endless pots of green tea. He speaks of markets, deals, potential business partners, he has traveled to the USA twice – and is planning another trip this summer. He likes America and its freedoms. He seems modern, open to new ideas and change, and yet sometimes he is surprisingly conservative, brutally canonical in his beliefs. He has found a good wife for his son he boasts: she is 16 he says, reads Namaz and wears the Hijab. They will marry in the Fall, when she will be 17. She will stop high school after her wedding, but will continue her religious education. He hopes to have a Muslim wedding for the celebration he says, “without dancing or music. Men will come in the morning and women in the afternoon.” Speaking with Fazlitdin is to feel comfortable and then suddenly homesick.

Over the two days spent with Fazlitdin, I will learn to appreciate these paradoxes, learn to accept the complexities of living in Marghilan – where religion and the preservation of customs is fought for with an impressive strength and vigor. Here in Marghilan I feel for the first time the religious and political power that craftsmen once wielded in their towns: in preserving conservative gestures, they are preserving the traditions that keep them alive. I come to believe that saving these values and traditions, brutal that they are, is perhaps the only way to preserve the town’s economic livelihood: the physical, demanding, slow, soft, hand-weaving of silk.

Marghilan’s Silk, hand-made from worm to beautiful liquid cloth seems to be reliant on resolute conservatism and the most traditional structures of Islam. In buying that tempting and magic cloth we affirm a way a life, we accept that there are different worlds. different values. It is an ode to the difference in the world: that variety that lets us dream. but within that giving in, within that acceptance of rules and geographies decided by others, I whisper: rebel sisters. rebel. knowing that freedoms can be acquired among the madness.

Near Histories

The Soviet Union was keen on breaking the historical resistance it faced in the Ferghana Valley – the hideaway for the Basmachi – those rebel warriors fighting the empire-builders to the north.

In Central Asia: 130 Years of Russian Dominance, A Historical Overview edited by Edward Allworth, the authors talk in great length about the resistance the Russians found in the Ferghana, with the first rumbles starting in 1885. Ten years later in “1895, a Naqshbandi Ishan from Andijan, Ismail Khan Tore, was arrested in Aulie Ata, where he was collecting funds to finance the holy war. (…) Three years later, May 18, 1898, it was again in Andijan that a revolt broke out which spread immediately to the districts of Osh, Namangan, and Marghilan. Leading it once again was an Ishan of the Sufi brotherhood of the Naqshbandi.”

“The consequences of the [unsuccessful] uprising were manifold. To the reprisals against the guilty were added “economic” disabilities upon certain villages accused of having lent too much support to the rebels. In the Marghilan district, several villages or hamlets were destroyed, their inhabitants expelled for having taken part in the revolt, and the population replaced by Russians who were allotted a great amount of well-irrigated lands, where they began growing cotton. The Central Asians were transplanted to barren lands and founded a new village, Marhamat.”

The Ferghana would continue to revolt into the late 1920’s.

But the Russians were determined to fortify their hold on the region. First, undoing the centrifugal position of Khokand with the new modernity of the Tsar’s regional center: Ferghana city. Then, busting up the networks of religious schools and leaders – the empire set about to its work of changing the region. Marghilan – the historical center of Islam in the valley was kept a close watch on and a tightly fitted lid was placed on the city and its leaders.

Private silk weaving was pronounced illegal – the practice was to be entirely focused in the city’s new factory. This was an economic decree set to also break the political power of rich silk merchants. Fazlitdin’s grandfathers, wealthy land owners and craftsmen – the merchant sovereigns of the valley - were stripped of their property and studios and forced to work in the factories.

The pressure, control and suspicion were too great and the family moved to Andijan where they were safer.

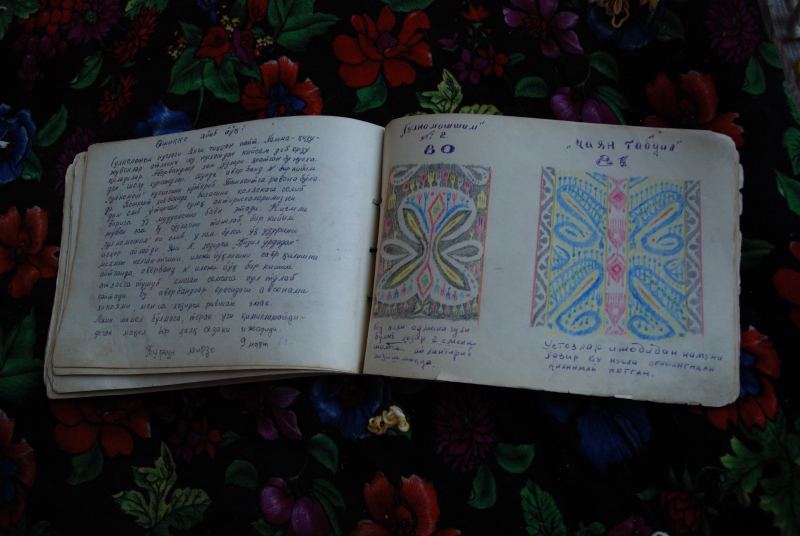

In Andjian, Fazlitdin recounts, the Marghilan weavers would unite and secretly continue the silk weaving in the homes of friends: an elite class whispering. As a child, he would be taken to these secret meeting rooms by his father, where they would stay for two or three days at a time. It was frightening Fazlitdin says. Many people were arrested for this kind of gathering, and there was always a fear that some passerby would hear the rhythmic swing of the silk loom in action and report their meeting place. These secret hideaways were enclaves of tradition: the humming of prayers, the secret hope for freedoms, the candles lit against the empire. These secret meetings were a time of teaching – and fathers passed onto their sons the craft of weaving and the beliefs of Islam: the bare essentials of bloodline traditions.

Master Mirzaahmedov was a pillar in Marghilan. A keeper of the faith, a master of silk weaving. For his secretly continuing to weave silk at home, resolute to keep traditions alive, he was sent to the desert prisons of Kashgardaria for six years.

The Fall

With the fall of the Soviet Union, Mirzaahmedov was released and returned home again. His genius and spirit were finally recognized with material success and official accolades. These men who live through hell and heaven. In 2005 he received the presidential award recognizing his work as a master, which came with a check of 7.5 million syms. (I don’t remember the exchange rate – but it’s a bundle of money). Mirzaahmedov grew his home-based business by welcoming tourists and demonstrating his traditional craft.

For Fazlitdin, an entrepreneur ready to revive the strength and power of his family, the fall of the Soviet Union was also a blessing. “For our family,” he says, “the collapse was good. Now, there are incentives for hard work, for business and building.” He believes that the collapse was also positive for the city of Marghilan. Indeed Marghilan has profited from the exuberant market for its radiant silks, and is now visibly busy rebuilding its mosques and medressas – although now under the paranoid eye and control of Islam Karimov, who perhaps more than the Soviets, fears the power of Islam. (many stories there. police. and freedoms hounded)

With the space and freedoms of the Fall, Fazlitdin has created a slow (steady) smart business. He opened his Ikhat National Craft Development Center in 2001 and has since then steadily increased the output and reach of his ambition. Today 30 people work in the center. Every month the center can weave 200 meters of silk. (beautiful) Around the center land does not lie fallow: orchards have been planted in every spare inch of land – Fazlitdin likes growth. There are no barren fields under his watch.

Fazlitdin’s quality is unbeatable in Marghilan. He has the best product – a reality clear to the touch. He sells his textiles to Tashkent, Samarkand and Bukhara traders who come place orders at the center. Tourists visiting Marghilan also add to revenue.

Generations have been reborn in the Dadajonov house success. Fazlitdin’s father still overlooks the silk production, while Fazlitdin trains his two sons in the business. He is tough on his sons, who listen in on meetings with clients and have learned most steps in the production, but who Fazlitdin says are simply not yet ready to take over. He’s hard to please. His sons have glowing skin. sharp. they are beautiful, but they stand at distance: the sons of the king. One of the employees (beautiful dark skin stretched softly on a tight architecture of muscle and pride) – a weaver – stands out among the young silk barons. He has learned almost all of the steps of the silk making and during the morning silk-dying, he leads the movement, his strength and confidence clear. Here the buds of battle: the pauper and the princes. Life among the routine of the everyday.

Silk and Saints

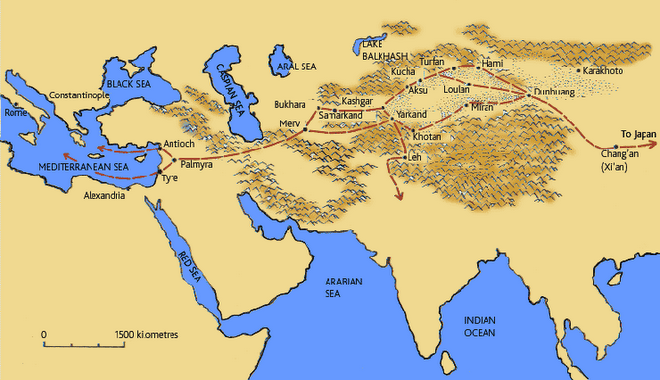

Fazlitdin tells about the history of silk. Silk was not born in Marghilan he says. It was first developed in Japan and Tajikistan he believes. Only then was it imported to the Valley. I ask him if there are any stories or legends about how silk arrived in Marghilan, but the history doesn’t roll off his tongue. He makes no mention of China and her rebel princess.

But he does tell us of the Prophet of Silk – Eyüp (in Turkish), Ayyub (in Arabic), or in English – Job, a major prophet in Islam.

In Marghilan, Fazlitdin tells us that – the once wealthy Eyüp came to the valley as a mendicant friar, riddled with sores and lesions. Eyüp never blamed God for his hardship and pain, and endured his chastisement so humbly that God rewarded Job’s patience by healing him with the waters of a sacred stream. From his sores, tells us Fazlitdin, silk worms fell to the ground. And so with his healing the patient prophet imported silk to the valley. Today Eyüp remains the protector of all who work with the fine material. His tomb (one of them) is in Bukhara, built on a spring outside the old Ark walls.

Looking on-line, I find some echoes of this story:

“At the end of the nineteenth century, German biblical scholar and linguist J.G. Weitzstein (1815-1905) traveled to [a] monastery near Damascus where he found Job’s tomb, his well, and the stone on which he sat on his dung heap. He also found several petrified rocks about which he tells us this:

While these people were offering up their Aur [afternoon prayers] in this place, Sa’d brought me a handful of small, round stones, which tradition declares to be the worms that fell to the ground from Job’s sores, petrified." (source: http://www.bibleinterp.com/articles/Vicchio_Image_Ayyub.htm)

Fazlitdin also tells as about the protector of silk designers: Baha’ Al-din Naqshbandi, the Hadith writer and founder of the Naqshbandi Tarikat - Sufi brotherhood. Born near Bukhara, Naqshband greatly influenced Islam in the region, and it’s not surprising to hear his name in Marghilan where Islam comes in concentrate – and where Naqshbandi leaders were once fermenting riots against the Soviet Empire. Naqshband’s name, Faztlidin tells us means, designer. It has also been translated as "related to the image-maker" or "Pattern Maker". Today, Naqshband continues to bring inspiration and health to the silk weavers, and he is venerated as a patron saint.

I wonder about the rites and rituals of the veneration – more to research here.

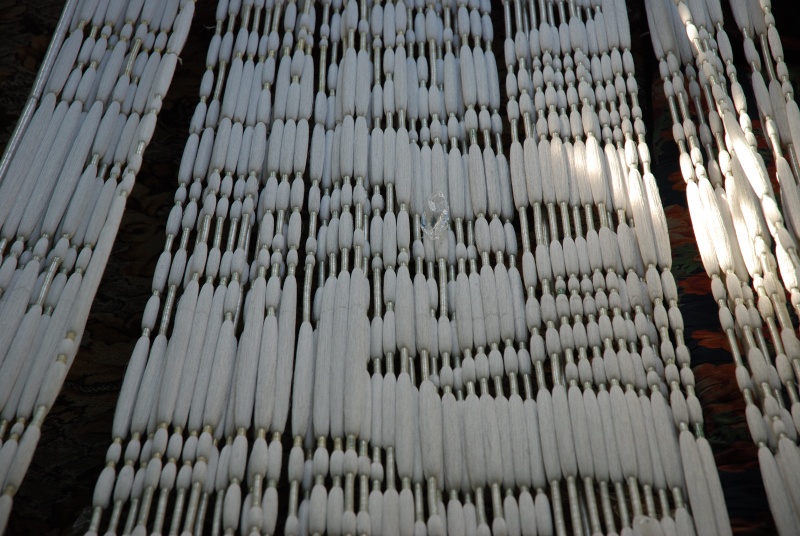

The Fabric

There are many types of silk woven on the rhythmic looms of Marghilan. Bakhmal – double-sided silk velvet, which all but disappeared in the 18th century to be famously revived by Mirzaahmedov Usto in the past decade. Shoye – silk, as we mostly know it: one color, light as the wind, fluid, ephemeral. And then there is Adras - local magic - called Ikhat in the West – that bold weaving of color, a kaleidoscopic look at angry cloud-covered sky pierced by sunlight, alive, corporal. I see in the colors, bright, daring femininity woven for the world; gifts of cloud and texture. Adr means cloud in Persian.

Here among the mosques; among the imams, the soul of the world pulsing. A colored map of emotions, sketching out that longing; that richness, ancient. In the patterns, the soft etchings of the older orders of the world – when we danced untempered by this cement and this speed and distance of movement. In the patterns, echoes of times past when we laid down among the chaos of Emirs and Khans.

Adras – bloodstained, crass, cruel, ash-strewn, salted, bitter, real.

There is order and science in the cloth. Children start to learn at the age of 10 or 11 and only the true masters will learn all the 18 stages of the fabric – from the pattern-drawing and tying, to the dying, the washing, the stretching, loom-setting, to the final weaving of string into magic. Only men can rise beyond the division of labor inherent in the 18 steps that start after the gathering of the mulberry leaves and the fattening of the worms. Silk is a commodity of power to be controlled by few. There are secrets still. Rules – that even the colors must follow: first the Whites, than the Yellows, Reds, Greens, Blues and then the darkest Black – for the tying and dying.

The dying of silk is work. physical strength demanded.

For Adras cloth, the threads are dyed and arranged into a pattern before weaving. This makes dying math. There are multiple colors baths during which the silk is taken off the design loom. Replacing the silk back onto the loom while respecting the pattern is about seeing the pattern in small signs etched on the threads. Signs of order and direction that help the artisan tie the strings back up to the design board, preserving the pattern. To this dance is added the wrapping and unwrapping of cotton yarn that protects the silk from being dyed by a certain color - tiedye fashion. Unwrap one color to dye another. Once dyed yellow – depending on how you wrap and unwrap you can get green, blue and yellow in the next color baths. exponential color. (it’s complicated, and my words are not helping.)

Futures

Silk in Marghilan has launched boldly into the market economy. Although it is difficult (expensive and paper-heavy) to export anything (except cotton and gas, I guess) from Uzbekistan, the local Marghilan silk-makers have more than taken advantage of the tourists that flock to Samarkand and Bukhara in increasing numbers. Fazlitdin is confident in the growth of his Ikhat center within the needs of domestic demand. He is also willing to brave the hassles and pressures of export and work with partners in the USA and Europe.

The continuation of Mirzaahmedov’s work is a little bit more precarious, although also carried by domestic demand.

Mirzaahmedov Usto died a year ago. He was a 7th generation weaver, grown up among the activity and sound of silk. In death, his spirit remains to walk the walls of the family home. He’s like a ghost here, palpable in the sadness. His family is still living off the gestures and traditions of silk weaving, but the links to traditions are slightly faded, a little tarnished. None of Mirzaahmedov’s sons have a passion for the craft and now a cousin, Mahmut Turzanov comes in everyday to run the workshop. Although Mahmut studied with the master for 15 years, there is a frailty to him, a childishness. These age old skills are precarious legacies. Here in the house of an old master is now the slow forgetting of ancient gestures.

Mirzaahmedov’s son is absent from the house and workshop – he wakes in the late afternoon and spends the nights drinking with his friends under the cover of darkness. He is not interested in carrying his family or its traditions. He’s young, perhaps he’s sick of all the weight of tradition. He’s obviously set himself loose from the rhythms and demands of the silk.

But the women of the house continue to carry the walls. The women are in charge here. There is Mirzaahmedov’s wife – fierce. She is tough, hard-edged, and has a piercing beautiful, almost violent look. She sees through me. (I’m tired and we maneuver around each other. Two centers colliding.) But she carries the business, intent on preserving the work of her husband. Kamberoy, Mirzaahmedov’s pensive beauty of a daughter helps her mother to keep the house and its tourist business running. Being the only daughter left in the house is no gift and Kamberoy work from dawn to late after dark.

The family has benefited from the new market for silk – silk tourism. Before his death, the master left both the tradition and the economic machinery to support his family: a tourist restaurant in his home, a silk gift shop and a potential guesthouse (the construction to be finished next year). Mirzaahmedov opened his home to tourists as early as 1992. The family then built their current larger compound to host the growing number of visitors. Now there are tourists almost every day, especially on Thursdays and Sundays when they come to see Marghilan’s bustling market. Their address is written in the French Petit Fute (the equivalent of the Lonely Planet) – ensuring a steady stream of French tourists. They are also in a Japanese guidebook.

While he mom hosts the tourists, Kamerboy makes sure that the long table on the veranda remains always prepared – ready to pour tea and serve cakes and candies. When the tourists leave, Kamerboy helps Mahmut in the strenuous work of dying and weaving. She looks absent, gone. Her heart is not in the work. She is burdened with the weight of legacies inherited: heir to a stumbling empire. There is a sadness in the house; a decay that I can’t quite get my hands on; a desperation. The master has left a castle ready to be deserted. Looking at Kamberoy I ache.

At night a soft cool and quiet falls on the household. The activity of the day over and gone: silence, a mother talking with her unruly son in the night. In the morning, the family will return – the daughter, the sisters, the cousins, all who work in the weaving and making of the family silk. All will fight again the weight of forces leading them away from a father’s work.