A red carcass, made from fire, wood, water and sweat. Its exterior made from the shepherd’s bounty: wool felt and song. The yurt is the center of life: a mobile hearth, the center of the nomad’s creativity and freedom.

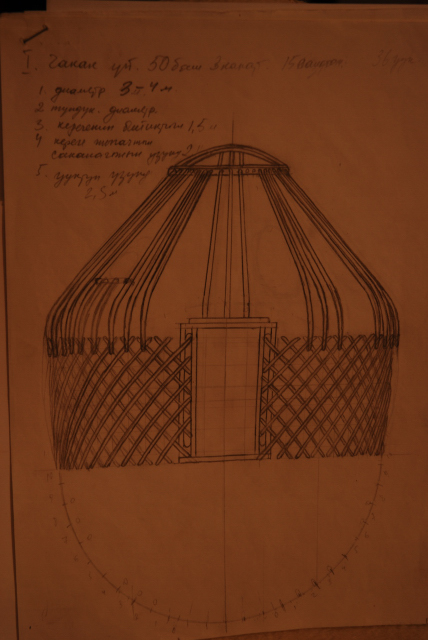

The yurt consists of many parts: the wooden lattice, the kerege, on which uuk, curved wooden poles are tied to hold the crowning cap - the tyunduk – which acts as both a window and a flue (chimney). The Chi, or reed wrapping, decorated with colored threads protects from wind and dampness. Thick pressed wool (felt) coverings wrap the outside, and then there are Alakiiz (multi-colored felt carpets), Shyrdak (the quilted/appliqué felt mosaic carpet used to decorate the walls and floor), Jabyk Bash (embroidered curtains for the Yurt door), Teigirich (the horizontally woven border decoration for the outside of the yurt), Tchachery, the woven interior decorations, and others still.

To make the yurt takes patience, skill, and soul.

It is a practical, functional home into which creativity and life are woven: Soul integrated into the daily life. The yurt is creation intricately intertwined with survival. It embodies the nomad’s respect for his world, the environment – and is made of all the elements in the proximity of the nomad: wood, wool, reed, water, fire, natural dyes. Simple, it is full of spiritual generosity: colors, symbols, forms, and patterns which unveil the spirit, soul and energies of the makers.

The whole expresses the world of the nomad, their freedoms and the harmony of their lives in nature. To pack it up and shift pasture lands takes a mere three to five hours. It is the embodiment of mobility.

The yurt stands at the intersection of science (architecture, form) and the enchantment of nature and spirituality. At its core is a lifestyle of meaning and unity with nature.

Kyyzl Tyy

I go to Kyyzl Tyy – a village of Yurt-makers with the golden-toothed Salkyn – my friend and interpreter from Bakenbaevo. We go meet the open-faced Gulbar and Sapar – a man and wife team. Sapar and his two sons build the wooden elements of the yurt, while Gulbar and three women from the village make the felt and reed elements that will decorate and protect the frame. The yurt is a union of labor, a union of the sexes – partitioned by separate tasks, but brought together in the whole.

Sapar and Gulbar make about five complete yurts a year, and about 20 carcasses – just the wooden frame. One yurt needs about 15 parts of felt, thick and sturdy to last a decade. The wooden frame lasts for two decades, outside in all the elements, it is built to last.

Sapar, now 54 has been making yurts since he was 12 years old, taught by his father. His is a family trade that has continued for multiple generations - more than he remembers. His grandfather also made jewelry. Sapar says that if his father had continued to make jewelry, he too would still make it, but his grandfather died while his father was still young, and the knowledge disappeared.

We sit down to tea. The cows are in the summer pastures – so there is no fresh milk, and we spoon powdered milk into our black tea.

The mosque calls to prayer, and Sapar’s two sons rush out of the studio. They are beautiful, tall and lean, with sun-kissed dark skin and sharp eyes. The mullah beckons and the sons run off to the mosque, where they pray five times a day. The mosque in Kyyzl Tyy was finished 3 months ago. Before, the sons would go every Friday for the Juma Namaz in the neighboring town. Now, proximity enables more fervent devotion. The mosque was built with Syrian money: new, shiny, calling. Gulbar and Sapar do not pray, but they are happy that their sons are learning. Gulbar says it will give them a good education and up-bringing, while keeping them away from alcohol, drugs and cigarettes – the common ailments of the village men.

Over the past decade, almost every household in Kyyzl Tyy has started to make Yurts. After the close of the Soviet Yurt factories (production was centralized), local and foreign demand for the portable hearths increased, and the whole village went to work. Mostly, they are exported to tourist centers, where travelers pay a steep price to experience the great wide. Some are still bought by local semi-nomadic shepherds.

Sapar says that ten years ago only five or six families made yurts, but today more than 100 families are involved in the trade. He does not think this will last, as many of the yurt-makers make sub-standard quality. However, in the meantime, the increase in production has put great pressure on the local willow trees used to make the carcass. Where once, Sapar used to just cut down trees from the neighboring forests, he now has to buy wood from Jetty Ogus, a valley about one hour from Kyyzl Tyy.

A Way of Life

But despite this boost in the local Kyyzl Tyy economy, today, the semi-nomadic way of life the yurt embodies is threatened. Urbanization and globalization are forever pulling people away from the nomadic lifestyle, luring them with tales of fabulous wealth, material goods and the unsustainable luxuries of our Western lives. (of course, there are many good things about our way of life: health care, education, travel and many others, but there are also many problems. here, I’m thinking about the problems). The Kyrgyz are increasingly sedentary – the impact of sovietization and today’s global world. They are losing touch with the land, and the symbiotic relations of man and nature are being exploded – worn down, strained.

Ak-Terek, a Bishkek based NGO supported by the Christensen Fund (“backing the stewards of cultural and biological diversity”) studies the traditional knowledge surrounding the yurt and the economy of the nomads – animal husbandry. The stunningly beautiful and soft-spoken director of Ak-Terek, Nazgul Esengulova, is worried that the links between generations are weakening, and much of the traditional knowledge of the pasturelands and the nomadic lifestyle are disappearing.

The biocultural landscape of the Kyrgyz nomads is shifting rapidly, perhaps irremediably. Nazgul tells of the extreme land degradation that the Kyrgyz herders have inherited from the Soviets. Focused on quantity, the soviets multiplied the amount of sheep herded on pasture-lands – thus draining the richness of the pasture soils. They ignored the traditional rotation of pastures, and brought scientific methods to the animal husbandry: vaccinations, calendars and time-tables etc. That delicate balance, and “ecoute” or listening of the land disappeared. Where once the grazing times and places were determined by knowledgeable/versed herders who could read the pastures by the appearance of certain plants and animals, under the Soviets, all pasture land was used to full capacity, ignoring the traditional signs of over-grazing etc.. Furthermore, in creating a commune, the Soviets took away ownership of the land, thus taking away the intimate link and responsibility towards the land. The commune broke that deep respect between a herder and his pasture.

Here ecology and culture collide. How we live – our cultural norms, lifestyles - impact our natural world. (why do we always need to look elsewhere to be reminded). It is an interesting field of work – understanding a biocultural landscape. a double lens of culture and science.

The delicate knowledge of the pastures’ cycles, including its shifting plant and animal-life have all but disappeared. Nazgul and her organization have worked with many of the herders around the Song Kul alpine lake. She speaks of an elder in Tuluk village, Albi Mahamat Ata, who at 84 still knows a lot about the land and its signs. But he’s getting old she says, and often mixes up stories, and slips and slides between realities. The elders are disappearing, and with them that sacred – incredibly ancient - knowledge. Today, Nazgul says, many of the young herders do not want to listen to what little traditional knowledge remains, they rely on science and technology. They now force open mountain passes with bulldozers, rarely rotate their pastures, and have short-term profitability goals.

Where we – the ultra-modern West - should be learning from nomads, they are unfortunately learning from us. Our rapid, secular, disenchanting worlds are conquering even these high-mountain pastures.

The yurt which is the physical embodiment of the nomad’s sustainable subsistence and spiritual world may remain – in museums and tourist destinations – but the real soul and indigenous traditions and knowledge from which it was crafted are disappearing fast.

I’m thinking about Dinara Chuchunbaeva who said that, “Today, the disappearance of traditional cultural values [is] precipitating the extinction of traditional skills and expertise accumulated for ages, handicrafts are becoming a rarity (…)”

Perhaps crafts can be saved, continued – but what about this soul, this knowledge, this lifestyle. Can we ignore this when working with crafts – the soul and values from which they emerged?