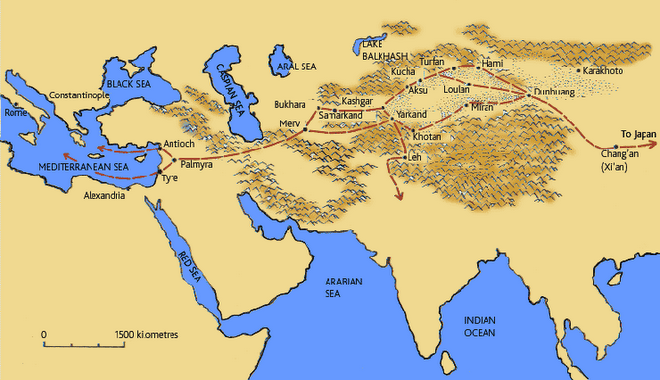

My first interviews with artisans are set around the traditional start of the Silk Route: Xian, the capital of Shaanxi Province. Below is the FOURTH of the series on Shaanxi Province.

Mountain Mud, Lions and Pepsi-Cola

It’s 7h45am and I am in a slow tractor of a bus. The thick morning mist still clinging to the soft new cement road, we are inching away from Zhouzhi towards Fengxiang – the ancient homeland of the Zhou dynasty emperors and a passage in the Chinese Classic Xi You Ji, The Journey West. Stepping in, stepping out, early morning workers become shadows on the tree-lined road. There are less mad trucks in the morning, and were it not for the pulse of the tractor’s motor and the rattling of its breaks, there would be a certain calm on the road. Behind me, women are talking about celebrations and wedding gifts: this year it will be a motorcycle for the groom. The bride’s family is paying. We inch ahead.

A little swerve – op-op-swoosh-honk-op-op! – we are overtaking a truck in a turn with little visibility, and of course the on-coming car is not slowing down – we make a last-second lunge back into the lane: a small reminder that every road in China is a hazard. Here highways are mass murders and small routes bandits always ready to ambush the weary driver. I have been told that road accidents are the second cause of death in China – with respiratory problems being the first, and suicide the third. But movement is necessary, not just for travel, but for development and the rising dragon that is China.

Roads and Religion

Pushing westward, I am entering the Da Xi Bu, China’s western more rural and underdeveloped provinces. Here, you start to remember the importance of roads – of pavement and easy access and departure from a place. In these ancient mountains on the border with Gansu Province, villages remain unconnected, distanced and thus left behind by the economic growth and flux of ideas that is changing China. A road is opportunity, it is ideas and information, an adventure with great potential. Recognizing the need to spread China’s new wealth, the Chinese government prioritized the development of the countryside in 2005 with the goal of building an equitable society and a “new socialist countryside”. This political effort has already been translated into concrete projects underway throughout the country. Everywhere roads are being built, connections made. I have been given a map of Fengxiang County by a friend in the provincial government. This is a futuristic map of the county painted with the more than 20 roads and highways set to be built within the next five years. Villages will be connected and neighboring counties will increase their porosity and exchange. Change does not come slow in China these days. My bus is now plowing through clouds of dust on the improvised side road, while the main road is being paved.

In the bus, my illuminated neighbor is driving me crazy. She is so excited that I am Catholic and has started to preach to me about love and Jesus – she is chanting – trancelike, repeating that Jesus has given her a new life. She feels connected with me. With the screech of the bus and the mass of people around us, I am starting to suffocate and want to tell her off. But, I pull myself together and kindly nod and acquiesce. She is part of the underground church and is an adamant missionary for her group. She asks me to join her the next day for prayers – she wakes everyday at 5:00am to pray for China. I kindly decline, wondering how God could possibly hear her prayers over the rattle, hum and bang of China’s thunderous growth. The factories that never sleep.

Some divine force has sensed my hostility and the bus suddenly pulls over on the highway. The driver tells me that we have arrived at my stop. Here - in the middle of nowhere, on an endless strip of cement busting through fallow land. This is the great highway drop-off. He points to the city beyond what seems to be miles of somber fields. There, he says, I can get my connecting bus.

Mountain Spirits and Roadside Crafts

Arriving in the late afternoon in Fengxiang, there is a good feeling in this ragged, lively town. Motorcycles and three-wheeled motorized cyclos race through the center’s four main streets, while night food stalls are filling up with customers. There is the bustle of Klondike days. Stores here sell all sorts of provisions – axes, ploughs, thick rope, canvas bags and seeds. There are Shi Huo drums and handmade crafts being sold on the streets – a good omen. I set out before nightfall to talk to some of the craftsmen.

The fifty year old Mrs. Fan is chatting with some customers on the wide sidewalk of Fengxiang’s main thoroughfare where she sells her wares. She comes to Fengxiang every year before the Spring Festival to sell her handmade paper-cuts, and this year she has prepared about 400 pairs depicting tigers, flowers, sparrows, children playing and other more intricate scenes of country life. Mrs. Fan sells four pairs of paper cuts for 1RMB (less than 20 cents). These same paper-cuts could easily be sold in Beijing for 20RMB, and perhaps up to the equivalent of 80RMB (10USD) in the States. Mrs. Fan will live with her relatives in the county center until she has sold all her cuts and will return to her village 40 minutes south of Fengxiang in time to celebrate the Chinese New Year. In a week’s time, she will have made a precious couple hundred Renminbi.

The fifty year old Mrs. Fan is chatting with some customers on the wide sidewalk of Fengxiang’s main thoroughfare where she sells her wares. She comes to Fengxiang every year before the Spring Festival to sell her handmade paper-cuts, and this year she has prepared about 400 pairs depicting tigers, flowers, sparrows, children playing and other more intricate scenes of country life. Mrs. Fan sells four pairs of paper cuts for 1RMB (less than 20 cents). These same paper-cuts could easily be sold in Beijing for 20RMB, and perhaps up to the equivalent of 80RMB (10USD) in the States. Mrs. Fan will live with her relatives in the county center until she has sold all her cuts and will return to her village 40 minutes south of Fengxiang in time to celebrate the Chinese New Year. In a week’s time, she will have made a precious couple hundred Renminbi. The Business of Ancient Traditions

The first barrier of mountains west of Xian, Fengxiang is the mythical homeland of China’s Zhou Dynasty – the warrior people who brutally conquered the Shang more than 1,000 years before the Christian era. It is one of the legendary heartlands of ancient China, a land of divination and inscriptions carved on turtle shells. This used to be the western frontier of ancient China, the edge of the empire. Today, it now sits on the eastern edge of the Da Xi Bu, but has retained its position as a boundary, a border – a place beyond which everything is different: the last green threshold before the Hexi Corridor and the Gobi. Only recently connected to China’s economic boom, it is also a region thirsty for growth and ideas. There is a palpable hunger and enthusiasm. It is a county full of ancient histories facing the pull and attraction of the modern.

20 minutes outside of the county center, the village of Liu Ying Cun has dug into its rich past of traditions and boldly entered China’s fierce commercial market. They have transformed the village’s talent for crafting traditional clay figurines into a flourishing business. Today, Hu Xin Ming is at the helm of the Nisu clay figurine market, selling more than 200,000 figurines in 2006.

The Nisu making tradition originated sometime between the Qin and Han dynasties, around 100 AD, and flourished some hundred years later during the Tang dynasty in 600AD. Originally made as funerary ornaments (zun zang), the clay figurines evolved into household vessels, story-telling figurines and later into children’s toys.

Nisu depicting gods and spirits such as Tudi Shen (the God of Earth), the Fu Lu Shou triad with the Gods of Happiness, Emolument and Longevity also known as San Xing (Three Stars), Cai Shen (the God of Wealth), Zheng Kui, Guang Yin (Buddha), and many others were placed around the house as auspicious objects at the time of the Spring Festival. The figurines were thought to help to bring peace, wealth and happiness to the home in which they were placed. Nisu also evolved to reproduce mythical figures from China’s history as well as characters from tales such as the Xi You Ji, The Journey West, or the Sanguo YanYi, the Three Kingdoms. These figurines were 20cm to 50cm in height, and were sold as a story-telling set, used by parents and elders to recount the ancient stories to their children.

Today, the story-board figurines and religious deities are very hard to find. The extraordinary market that the village of Liu Ying has created for its Nisu has not developed these older more superstitious objects. These figures are also more delicate and time-consuming to make: crafted one by one, hands must be agile and gifted to roll, punch and pinch the soft wet clay into lively evocative figurines. In Liu Ying Cun, Mr. Du Ying is one of the few artisans who can still make these figurines. He can make a full set of these hand-made beauties with several weeks advanced notice, the price of which must be negotiated directly with him.

As more parts of the sacred slowly evolved into the secular, Nisu makers also began to depict countryside animals such as cows, horses and pigs, while still continuing to make mythical animals such as dragons and phoenixes. Made in all different shapes and sizes, these animal figurines are called Za Huo, sundries or assorted merchandise. A smaller, more refined version of the Za Huo emerged particularly for children, and included rattles, small bird and tiger figurines, as well toys depicting the 12 animals of the Chinese Zodiac. These smaller more intricate and refined Nisu are called Yao Huo.

Today in Liu Ying, the most frequently found Nisu are of the decorative variety – they are hollow figures made by pouring clay into thick flat molds. If the clay figurine is three-dimensional, two molded pieces are glued together with small strips of clay before baking next to the charcoal oven. Once heated and dried they form a soft white shell, smooth like plaster. The dried product depicting lions, tigers, dragons, or the 12 Zodiac Animals are then painted in bright colors and shipped to destinations around China. This year, Liu Ying Cun was invaded by thousands of ceramic pigs, some lying outside to dry, while others were being hastily painted inside the village workshops, to be shipped in time for the new year of the pig.

The economic viability of the Nisu has insured that future generations are actively learning the trade, and in most of Liu Ying Cun’s workshops there are three generations working together to craft the clay lions and colorful pigs. The heads of the most successful workshops have become definitive heroes in Fengxiang County – they are the entrepreneurs that have effectively revitalized one of the county’s oldest traditions.

Craftsmen as Entrepreneurs

The 77 year old Hu Shen is one of these heroes – whose renown was further expanded in 2001 when his clay figurines were featured in a nationwide series of postal stamps – of which he will very happily give you a commemorative postcard. Mr. Hu’s family has been in the Nisu business for 600 years and before the Cultural Revolution, the Hu family ran the town’s most prolific and renown Nisu workshop. They would make Nisu only in the wintertime when the planting and harvesting was over. Nisu was a supplement to their family income, and was never considered a year-round job. During the Spring Festival or to celebrate a baby’s man yue – first month, villagers would come to Hu Shen’s house to buy the figurines, or go to the Miao Hui, the temple fairs, where Hu Shen and his brothers would go to sell their family’s Nisu.

The 77 year old Hu Shen is one of these heroes – whose renown was further expanded in 2001 when his clay figurines were featured in a nationwide series of postal stamps – of which he will very happily give you a commemorative postcard. Mr. Hu’s family has been in the Nisu business for 600 years and before the Cultural Revolution, the Hu family ran the town’s most prolific and renown Nisu workshop. They would make Nisu only in the wintertime when the planting and harvesting was over. Nisu was a supplement to their family income, and was never considered a year-round job. During the Spring Festival or to celebrate a baby’s man yue – first month, villagers would come to Hu Shen’s house to buy the figurines, or go to the Miao Hui, the temple fairs, where Hu Shen and his brothers would go to sell their family’s Nisu.Specializing in the creation of mixing ping, superstitious wares, Hu Shen’s family was naturally targeted during the Cultural Revolution. He and his father were forced to stop their craft and work everyday in a county factory, after which they had to perform self-criticisms on a nightly basis. At that time however, Hu Shen and his father continued to secretly mold clay into all sorts of shapes and figurines. Because they could not produce too many pieces, each piece was made to perfection, twisted and turned, folded and kneaded with precision: ten years of patience and endurance.

Hu Shen takes me to his workshop’s attic and we snoop around piles and piles of papers, broken clay figurines, sheets covered in thick white dust in search of the family’s old molds and figurines. Hu Shen finally finds a box of old figurines, dating from the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). They are intricately crafted and are the characters in an opera story – whose name I unfortunately didn’t understand. Behind each figurine, Hu Shen’s grandfather has written the name of the character in red ink. Hu Shen tells me that there are three important reasons behind the making of these figurines: the first is to keep the story alive he says, the second is to inspire artistic creation, and the third is to help recount the stories to children. The figurines are the vessels of these ancient stories and beliefs, replicated and remade generation after generation.

Hu Shen laughs and tells me that if I had come when he was a young man, he certainly would not have shown me these figurines, or the molds and heating techniques that he uses to make the Nisu. These were family secrets he says: family secrets to be kept by the men in the blood line. If you teach your daughter the craft, he explains, when she marries she will bring this knowledge to another family who may steal your business. To keep the knowledge in the family, women were kept in the dark about most of the production process, and were able to help only in putting on the final color touches. Today, he says much has changed and all his daughters and daughters-in-law are key parts in the family’s Nisu business.

Down the street from Hu Shen’s workshop are the headquarters of the 42 year old Hu Xin Ming, the actual King of Nisu who runs the most prolific and successful of Liu Ying Cun’s Nisu workshops. Hu Xin Ming tells me that creating a successful business was not a piece of cake. In 1979, with the start of reform in China, there was no sufficient infrastructure or technology to make or sell enough Nisu to make a living. There were only 10 families still making Nisu. He remembers that in 1979 a group of French researchers came to visit Fengxiang for one day, and the county built and paved a road for their arrival. Each village had to “clean-up” and get ready for their visit. At that time, the Nisu market was still very local, with no business beyond the county limits. Between 1980 and 1988 however more families started to make Nisu, until the Nisu market suddenly collapsed in1988: few people in the local market were buying the figurines, and the final product was too brittle to be exported to other cities. On arrival in Beijing or other cities too many of the figurines were broken. In 1996 however, with the support of the government, Hu Xin Ming created a new better clay technology and built a little workshop to revive the Nisu craft. By 2006, more than 80 families in Liu Ying Cun were making Nisu.

Down the street from Hu Shen’s workshop are the headquarters of the 42 year old Hu Xin Ming, the actual King of Nisu who runs the most prolific and successful of Liu Ying Cun’s Nisu workshops. Hu Xin Ming tells me that creating a successful business was not a piece of cake. In 1979, with the start of reform in China, there was no sufficient infrastructure or technology to make or sell enough Nisu to make a living. There were only 10 families still making Nisu. He remembers that in 1979 a group of French researchers came to visit Fengxiang for one day, and the county built and paved a road for their arrival. Each village had to “clean-up” and get ready for their visit. At that time, the Nisu market was still very local, with no business beyond the county limits. Between 1980 and 1988 however more families started to make Nisu, until the Nisu market suddenly collapsed in1988: few people in the local market were buying the figurines, and the final product was too brittle to be exported to other cities. On arrival in Beijing or other cities too many of the figurines were broken. In 1996 however, with the support of the government, Hu Xin Ming created a new better clay technology and built a little workshop to revive the Nisu craft. By 2006, more than 80 families in Liu Ying Cun were making Nisu.Hu Xin Ming now employs 30 people in his workshop, each making at least 10 pieces a day. In the early 90’s he was making 50,000 to 60,000 pieces a year. Today he makes up to 200,000 pieces a year. He is building a new factory at the entrance of the village where he will at least double his production. When I enter Hu Xin Ming’s workshop, he is sending a fax to clients. He does not need to go seek out his clients; they come to the village or go on-line to make orders. His biggest clients are large companies, who buy his decorative figurines to send to clients. In 2003 for example, Pepsi-Cola China bought 60,000 clay figurines packaged in red felt gift boxes. Hu Xin Ming is in the handicraft business, but his workshop is a modern apparatus with a global reach.

The Fengxiang Nisu production is the county’s showcase for craft-revival, and the pride of the local Cultural Association (Wen Hua Guan). I think mostly that it shows how one passionate man can revive a tradition through successful entrepreneurship and feeling out the changing appetite of current and potential customers. The craft has brought an impressive vitality to Liu Ying Cun, bringing wealth, opportunities and exchange with people from all over China. Hu Xin Min’s new factory will certainly continue to bring wealth to the village, and perhaps even help them to further diversify their offering.